True story: Along with a standard thank-you note, I once mailed a bottle of Windex to a Cornell University administrator who had interviewed me for a management position. The bottle was bedecked in a gold bow. I asked her to give it to an hourly employee whose name I remembered because his greenhouse section was the cleanest of the 15 I walked through. That fellow emailed me grateful thanks for noticing his work. The administrator offered me the job.

My commitment to sanitation goes far beyond being meticulous. The neat freak trait is a good one, as is even paranoia, perhaps, because so much of what we battle with grow room sanitation lurks invisible to the naked eye.

Like much of my management experience, this cleaning habit was learned the hard way. At the growth facility I managed in West Lafayette, Ind., we spent one disastrous summer discarding valuable research plants—some irreplaceable thanks to their genetic modifications—due to an incurable viral disease. The disease, Impatiens Necrotic Spot Virus, can only be spread by feeding the common greenhouse pest, western flower thrips. Each faculty member had their own grow room, and they continuously cropped for years, meaning these particular greenhouse rooms were never emptied and cleaned. New seedlings were placed next to maturing plants. This resulted in persistent thrips, excessive chemical spraying, inevitable pesticide resistance and more thrips. The pest cycle was never broken. Once the virus entered, it ran rampant through the susceptible crops.

We learned that summer that it was best to have communal rooms where researchers shared space, but that space was divided into growth phases so each room could be sanitized following seed harvest—about every four months. This hard lesson, coupled with other painful ones involving tobacco mosaic virus and powdery mildew diseases, made us sanitation experts. We experimented with methods, tools, environments and chemistry. We were given advice from that special brotherhood and sisterhood who manage plant-growth facilities at universities across North America. What we learned can be helpful in developing or streamlining your sanitation protocols.

Start with a Scorched Earth Policy

For being a horticulturist, you’d be surprised how beautiful I find an empty grow room to be. Our pest scouting indicated that a few days of being empty resulted in two months of pest control in a greenhouse, longer for a grow room that was better-sealed from the outdoors.

First rule: Empty means empty. The equipment can stay, but all vestiges of life need to be removed. Every plant, every leaf, every scrap of root substrate. And one step further, what sustains life: water. You need to dry out the place so that any insect and disease life that rely on water will perish. Even pressure wash that nasty crud in the drain.

To accomplish this, invest in good shop-vacs and pressure washers. We learned that it paid to have two shop-vacs, clearly labeled for their use-one “dry” and one “wet.” In most models, the dry vacuuming requires a dust filter over the intake inside the machine. If this filter is left in for wet operation, it becomes caked with mud, which lowers airflow. You’ll have a mess when the clock is ticking to get the room back in production.

Depending on your facility’s size and type, you may need two pressure washers. A small electric one is lightweight and effective for most cleaning, but, its lifespan is greatly diminished if used for more than 30 minutes at a time. A gas-powered pressure washer can run for extended periods and is typically more powerful. For safety reasons, though, you can’t run a combustion engine inside a closed space. We were able to use one with a 50-foot hose extension by parking it outdoors. Pressure washers with oscillating nozzle heads, such as those made by Karcher, were most effective, especially at cleaning algae stains.

Take care not to permanently scar the cement with a pinpoint stream, and users should always wear safety glasses—not splash goggles that fog up—or a face shield, and hearing protection. Provide your workers with two pairs of shields or glasses so they can rotate in case of lens fogging. Otherwise, they’ll just take them off when you’re not around.

All this work is for naught if you leave any plants or pots of used root substrate. Even if it’s legitimate breeding stock, you can’t keep it in your production area, as it will be a pest reservoir. You’ll need to find a separate space to house those long-term plants, like how a university designates a “collection” house for such stock material.

If you are in a greenhouse, this is also the time to kill those weeds hiding in cracks. There are some herbicides labeled for greenhouses (please read and follow all label instructions if you use an herbicide), but if you are pesticide-free, you’ll need to pull them or use some other remedy. More often than not, you’ll find insects on these weeds.

The next step is to remove debris. Using a hose attachment or pressure washer, start with the walls and growing tables and work your way downward. Scoop up that debris or direct it to the drain if you have a soil trap you can remove it from later.

Keep in mind that you are not just removing debris, but dislodging disease spores from surfaces and two-spotted spider mites that have gone into a hibernation phase, or diapause. These mites crawl off into dark cracks and crevices only to re-emerge later. During this phase, they do not feed, and predator mites have difficulty finding them. If your team understands what they are going after during this cleaning, they will do a better job. Make it a point to be pleased with a spotless room, rather than let this opportunity to reward good work pass unnoticed.

The Bake-Out

During the bake-out phase, the goal is to heat the room to kill spores of powdery and downy mildews, and to remove all moisture sources that could sustain remaining insects. Our heat prescription was six hours at a minimum of 95 degrees Fahrenheit for mildew control. If you are able, you can increase temperatures up to 105 degrees, but any higher will have a detrimental effect on some electronics, seals within components and curtain fabric. Following that heating, lower the temperature to between 80 and 85 degrees and hold it for as long as you can afford to keep the room empty.

I strongly recommend maintaining that temperature for at least 24 hours, including the bake-out. Three to five days would be ideal to chase out or kill most active insects without a water or food source.

Personally, I don’t see the point of trying to clean and replant a grow room in the same day, as the benefit in crop cycle time would be lost in crop quality and labor hours dealing with a pest problem later. During this drying down, lock the room to keep people out and remove drain covers to hasten drying.

Finding the Right Formula

Chemical disinfection can be performed before the heat treatments, or just prior to new plants being moved into the grow room. I prefer the latter for two reasons. First, to eliminate any accidental contamination that may have happened during the dry-down. Second, because the smell of a disinfected room reminds everyone who enters of the work put into achieving this level of cleanliness.

Many commercial products are available for disinfection of greenhouse and grow-room surfaces. Reading the fine print on the product label is necessary to determine which product is both legal and most appropriate.

Chlorine products, such as bleach, are legal for food production areas like commercial kitchens, but are not EPA registered for greenhouse production. For this reason, I would advise against using bleach in your plant-growing areas. Besides, there are much better products that are safer for eyes and clothing.

For ornamental production, I have effectively used Virkon S, a poultry and swine production disinfectant; the quaternary ammoniums Green-Shield II and Physan 20, and the peroxide formulations ZeroTol 2.0 and OxiDate 2.0. However, only one product, another hydrogen peroxide product called SaniDate 5.0, is labeled for greenhouses, farms, food production, preparation and storage areas, as well as hospitals and pharmaceutical-processing facilities, and is certified for organic production.

A stronger version of the agent, SaniDate 12.0, is labeled for disinfecting and clearing biofilm from irrigation lines. But it is not labeled for all the uses of SaniDate 5.0, which can also be used for this purpose.

For irrigation lines, follow the directions for concentration used, and allow the solution to stand in the lines for a minimum of one hour, preferably overnight, then flush lines with clean water. SaniDate 5.0 can also be used for disinfecting evaporative coolers. Avoid further confusion with the sister product, OxiDate 2.0, which is formulated for direct application to plants for disease control.

Equipment to Get the Job Done

SaniDate 5.0 should be applied to surfaces and equipment at a dilution of 1:256, or 0.5 fl. oz. per gallon with water. It can be applied with a hose attached to a portable injector such as made by Dosatron or Dosmatic. A simple hose nozzle that can change the water-stream pattern will help with broad sweeps and for reaching high corners.

Use injector units for this application instead of brass siphon mixers, as siphons have proven unreliable in my experience.

For small areas, one tool I’ve found useful is a Hudson Self-Mixing Sprayer that attaches to the end of the hose. It’s a bit like a foliar feeder that you use in your garden, but can be adjusted for siphoning ratio (i.e., it dispenses the SaniDate at the proper ratio, so the concentrate can be poured into the sprayer reservoir without dilution). The advantage is that you can pour the unused concentrate back into the original container when done since it has not been diluted. With techniques using a coarse spray from a hose, apply the solution to the walls, but not so high that the applicator will be back-splashed. (For those high parts, the heat treatment should be adequate; it is less likely to be contaminated and not worth risking the applicator’s safety if you don’t use a pressure washer.) Surfaces must remain wet for 10 minutes for proper disinfection, so you may need to go over each surface twice. A foaming agent, such as BioFoamer by BioSafe Systems, can lengthen the dwell time of the sanitizer, speeding up the process.

If you wish to reach the ceiling (again, heat treatment is typically sufficient), it is best to use a pressure washer that has a chemical injector. We use common sense where we spray. We turn off grow lights and avoid wetting them. We do not spray shade or light deprivation curtains, as the force may damage the material, especially if it has grown brittle with age. A fog applicator generates a cloud of floating droplets of chemical to reach all surfaces, including ceilings—while hastening application—improving dwell time and eliminating the strong force of liquid sprays. I prefer cold auto-fogging units, such as those made by Dramm, as they are also suitable for many microbial pesticides and they can be activated by a timer after hours so that no one is exposed to the chemical.

No matter which method you use, do not rinse the product off the surfaces. Bar people from entering during application, and follow all ventilation requirements (for fogging) and re-entry restrictions.

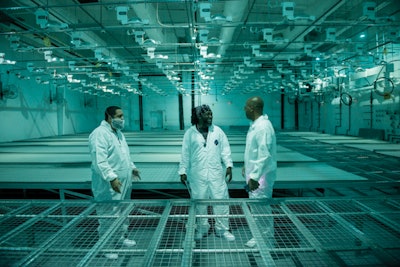

The Christening of the Grow Room

As you begin using the room, be sure to return all environmental settings to their correct values for optimum plant growth. Replace the drain covers if you removed them, and use this moment to realign tables, look for tripping hazards and other safety issues. On your marker board inside the room, post the date of last sanitation. Take the time to inspect the room personally, preferably with your team there. Reward them with a good word. Then make sure everyone knows that only new plants should be brought in.