I rang the doorbell to the nondescript, red-brick, somewhat industrial-looking building along the outskirts of Denver, aware of the camera above the door. As many of you know, it was all standard for a visit to a cultivation facility — the doorbell, the camera and the non-descriptness. Not just anyone can walk in the front door, everything has to be monitored, and no one wants to necessarily advertise what’s inside.

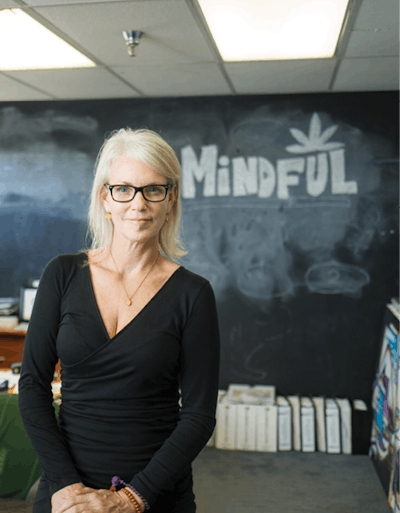

After being given a visitor badge, I waited on a low sofa for Meg Sanders to meet me in the lobby. Minutes later, Sanders came out and led me to her office. She is tall and blonde, wore all black, and had her own name badge hanging from a lanyard around her neck. (She would later explain that she couldn’t remove the badge, even for the photo shoot for the magazine cover, while she was in the facility. Compliance tops everything.)

Her office was spacious, but not grandiose, especially for the CEO (and one of three managing partners) of a multimillion-dollar company (nearly $18 million in 2015 to be exact); in fact, it had a professional coziness about it, with art on the walls, plenty of light and pictures of her two children on her desk.

Just outside was a conference room and other offices. The whole space was well-designed, clean, bright and professional. I could see why the media — including “60 Minutes,” The New York Times, Rolling Stone, National Geographic and The History Channel [“The Marijuana Revolution” show aired in January] — has been drawn to it and its cultivation space. It is a great portrait of a legal cannabis business, and one that likely would quell many misperceptions that linger among portions of the American public who still are skeptical, even fearful, of the plant and the industry building up around it. This is no illicit grow.

Inside Sanders’ office, the far wall was painted with chalkboard paint, and on the wall was a very large “Mindful” logo drawn in chalk.

I would soon learn that branding was a priority for both Sanders and the company she spearheads, and that the company’s name held particular significance. And the logo seemed to hover on the wall, exerting its presence over the business.

The name seems fitting. The important things to be mindful of in this business can be mind-blowing.

To start, as Sanders says, “This is a brand new industry. This won’t happen again in our lifetime.” Mindful is a pioneer among pioneers, going where virtually no (legal) entrepreneurs have gone before. It is paving the way through the waning era of marijuana prohibition and frequently changing regulations.

Then there are the patients, which Sanders says rank highest among priorities for the 6-year-old company, which operates the cultivation facility and four dispensaries in Colorado. Medical cannabis is where the company’s roots and 75 percent of its business lie, and Sanders seems content with this mix. “When I’m so exhausted, and I think, ‘How am I going to wake up the next morning?,’ and ... a patient who is going through some really horrible things comes up to me and hugs me, and says, ‘Thank you for being here.’ You remember what you are fighting for.”

The “fighting” is also on the list of things of which Sanders — who served as the only industry representative appointed to Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper’s 24-member Amendment 64 Task Force, charged with implementing the state’s recreational market — is mindful.

“People have this notion that you’re either a businessperson or an activist. We’re both,” she says. Sanders, who is a member of the Cannabis Business Alliance (the industry’s self-proclaimed chamber of commerce), explains that the company dedicates what she says is a “huge commitment of resources” to advocating alongside patients. The company has spent millions of dollars on this commitment over the years, according to Erik Williams, Mindful’s national director of government and public affairs, whose job is dedicated to this.

Sanders also travels around the country to educate and advocate. “Patients alone [lobbying] isn’t always enough. We want to be there to say, ‘Here’s what it means to be a business in the state,’ … and to help legislators look at it a different way,” she says.

The company, whose cultivation facility is across the street from one of the largest police stations in Denver, also tries to help the city’s police better understand the industry. “Some officers use Mindful’s facility for training new officers, so they know what a legal, professional operation looks like,” Sanders explains.

“Ultimately,” though, Sanders stresses, the company chose the name Mindful because it “represented how we run our business. It embodies what our view of cannabis could and should be.”

‘What We’re Doing Seems to Be Working’

The most important thing to be mindful of, however, is really the bottom line, right? After all, good intentions can inspire a business, but they can’t sustain it alone. Fortunately, Mindful has been doing a few things right on this end as well.

The state-of-the-art cultivation facility now spans about 32,000 square feet, nearly 75 percent of the 43,400-square-foot building. At its 2010 launch, the grow took up just 10 percent of the space, Sanders recalls.

Also, Mindful is moving its infused product business to a new Denver location that will house additional grow space.

Its dispensary business continues to expand as well. It launched its fourth dispensary (in Black Hawk) in December 2014, and now is anticipating the opening of a new dispensary in Addison, Ill., in Q1 this year. (Illinois has no restrictions on non-resident ownership.)

The number of Mindful employees has grown by nothing short of leaps and bounds, from 60 employees in early 2015 to 107 employees today.

One area into which Mindful is expanding — launching a consultation business — seems to be a growing trend among cultivators. The new business, called Marimind, is already pursuing opportunities in several states, working on legislation to help medical marijuana pass. It also is pushing its “SOPs, our way of doing things,” Sanders says. “Everyone has their own way of growing tomatoes, and they think it’s the best. We look at data — grow data, all aspects of input measurements and results, strain data, potency levels, harvest results, room performance by strain — and all the different technology we’ve tried, and what we’re doing seems to be working.”

Marimind also will help businesses that want to be customer-focused. “This is even more important when it involves patients,” says Williams. “One of the worst places where you want to have growing pains is with the customer experience. Mindful is very experienced there.”

‘We Didn’t Know What We Didn’t Know’

The decision to launch a consulting arm was motivated by mistakes made along an untraveled business path. “We kept seeing others make the same mistakes we did years ago,” says Sanders.

Among the mistakes, notes Williams, was not building enough of a time and financial cushion “in this new industry where you didn’t know the next regulation or rule change,” he says.

“With any construction/expansion project it always takes longer and costs more than you anticipate,” Sanders says. “In this business, it seems that is even more the case; budget time and operations capital accordingly!”

Mindful went through “several iterations of grow rooms,” she notes, and ran into “enormous challenges that no one could have predicted. These lessons we have learned over the past five years are being repeated every day across the country, and it is frustrating to watch.”

One serious challenge the business faced was one that plagues many startups: “a reasonable payroll budget in CAPEX (capital expenditures) development,” Sanders explains. “My partners and I went a very long time not getting paid, or being paid nominal amounts. It takes a toll, adds to additional stress of an already stressful situation. As skilled as we were in our pro forma and CAPEX budget, we didn’t know what we didn’t know. This is a brand new industry.”

“Little” costs also added up. “Each light is $700 a pop,” she says. But Sanders says the “ever-changing regulations, zoning rules and building department issues” are among the biggest challenges. For example, she recalls, “We had our extraction room engineered, peer reviewed, certified, and spent a ton of money on it, and now we have to change it based on new rules.

“When we first started out, there wasn’t zoning that addressed our industry,” she says. So while Mindful sought approval on everything, from the fire department to building inspectors, approval turned out to be a more transient concept. “We had ballasts — the brain that tells the lights to turn on, that talks between the power source and lights — in the room, and in our final inspection, the inspector said, ‘You can’t have those there; you have to have them outside the room.’ So we had to move them outside the room and get these special cords made to run from the ballasts to the lights,” Sanders says. “And now, of course, they can be wherever you want them to be!”

The unchartered territory and the integration of this still-infant industry into existing business and community services is bound to suffer ample growing pains. “Everything was growing so fast, and we were all moving so fast,” she says.

The best advice Sanders can offer others is: “Start talking to people in the building departments early on. Show them your plans, etc. It is so important.”

‘We’re Missing the Sergeants and the Colonels’

In what has been called the fastest-growing industry in the country, much talk has centered on the number of jobs being created. Mindful’s more than 78 percent employment jump in 2015 alone exemplifies this. But personnel has actually been Mindful’s biggest ongoing challenge.

It’s not just that there are more jobs than people to fill them, though Sanders says Colorado’s (and especially Denver’s) job market has become extremely tight; “this is an industry absent experienced middle management,” she says.

Mindful has a strong executive team with great experience, and, says Sander, “we have a boots-on-the-ground workforce at the retail and cultivation level. So what I’m missing are the sergeants and the colonels. The gap in between is an organizational chart killer.”

High competition for skilled employees compounds the problem. Potential middle managers “[have] kids, they’ve got spouses, ... insurance requirements, ... 401(k) needs,” she says.

While Sanders says that Mindful has an HR department, and benefits including a retirement plan, getting job candidates at that level to jump into a startup in a still federally illegal market is not easy. “In a start-up stage of a company, it would be ideal to do stock options,” Sanders notes as one example, “but we can’t do that right now, because it would be a massive mess from a compliance standpoint.”

Another challenge? The cash-only nature of much of the cannabis market. “It’s very challenging to refinance or buy a house if you’re in this industry. You need a year of bank statements, W-2s, proof that you pay your taxes, etc.,” she says.

The ‘Cake Boss’ of Cannabis?

Despite unexpected and significant ongoing challenges, Sanders has her sights set on continued growth and a pretty lofty goal centered, again, all around the Mindful brand. “We have a bigger vision than just having one dispensary here and another there.” One of the company’s goals, she says, is to have a national footprint. “I think it’s a value-add that not a lot of companies are focusing on right now.”

And by national footprint, she means making Mindful a sought-out destination in each state where it has retail locations, much like the “Cake Boss,” she says. “Very specific brands like the ‘Cake Boss’ have done a really good job that makes people feel like if they miss this, they’re missing a very good experience during their visit to the state.”

Other cannabis companies “might have a bigger grow or more locations,” Sanders notes, “so it’s very important to us to make sure we nail that [brand awareness] now. There’s a point in time where you have to nail it or you miss it.”

Beyond the recognizable logo and its omnipresence, “Mindful’s competitive advantage is our intentional way of doing things,” she says. “Mindful is a way of life, enhanced by cannabis. Everything we do — from how we treat our plants to how we treat our team members, customers and patients, to our work with local government and the community — we do to create a thoughtful experience that can be unique in this space.”

In addition to its patient advocacy efforts, it offers low-income (sometimes free) options for medication. It also supports the local chambers of commerce and shops locally, whenever possible, such as using local contractors and advertising agencies, and supports local charities. It participates in Wounded Warriors by teaching veterans how to garden and helping them establish home gardens, and supports the relatively new nonprofit Edipure Foundation for Hope, which aims to ensure access to high-CBD medications for those who need it.

The company has even started its own efforts, including the Little G Foundation — a 2,400-square-foot garden that Mindful created adjacent to its cultivation facility, where it grows vegetables for the community and its employees.

Being Top of Mind

We head back to Sanders’ office after touring various cultivation rooms — those where the moms are housed and cloning is done, others where flowering takes place — and I take of my lab coat (given to me before entering any of the grow rooms) and name badge. I catch a last glimpse of the chalk Mindful logo as I head out to stop by Mindful’s dispensary on Denver’s Colfax Ave.

The dispensary is easy to spot, with the large Mindful logo again big, bold and impressive. Inside, the shelves behind the counter are filled with Mindful gear — such as hats and t-shirts — and the logo seems to be everywhere.

It’s been weeks since my visit to Mindful, but I can still picture that logo. I’m sure the “Cake Boss” has a logo, though I can’t recall what it is. Maybe you can. But I think Meg Sanders and Mindful may just be on to something.