If you’re an entrepreneur in the cannabis industry, you already know that opportunities to invest in the fledgling sector are on the rise, driven in part by startups going public to capitalize on pools of investor dollars. Going public can be daunting—and that’s if you’re not in the cannabis industry. Toss some indica and sativa in to the going-public mix, and it can both add to the challenge and draw some extra attention and dollars. It’s not for everyone, and right now, the path is being forged by a relatively small number of cannabis companies.

Kaya Holdings [OTC.QB: KAYS] is one of those trailblazers. It’s one of several hundred publicly traded companies in the U.S. cannabis market, and the first fully reporting public company to own and operate a seed-to-sale legal marijuana business.

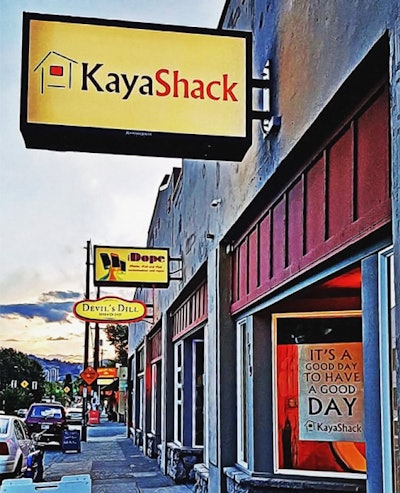

Kaya Holdings encompasses subsidiary Kaya Shack, which encompasses medical marijuana growing operations and a flagship medical marijuana retail store in Portland, Ore. Kaya Shack also manufactures proprietary cannabis products—such as a strain called Kaya Kush and one that is incubating, called Unicorn Delight—and conducts research and development into cannabis strains used for pain relief and disease treatment.

Its founders were motivated to go public because they saw opportunities to bolster their business, and for investors, and with aspirations for nationwide expansion, extra capital was a major upside. By going public, “we have set up the mechanism for pretty much anybody to call up a broker or go online with $1,000 or $100,000, and be a part of it,” the company’s chief executive officer, Craig Frank, says.

From Private to Public: The IPO

Generally speaking, initial public offerings, or IPOs, are how private companies become public entities. An IPO establishes a market for a company’s shares and allows the investing public to purchase a small piece of ownership in the firm.

Approximately 300 publicly traded cannabis companies now exist in the United States, up from 13 in 2013, according to a June report in Fortune. Among those 300, 40 raised a total of $95 million between Q1 2014 and Q1 2015. Most companies in the sector are penny stocks, trading for less than $5 per share.

Now, the phrase “initial public offering” may conjure images of corporate types in expensive suits ringing the opening bell at the New York Stock Exchange. If your company’s name is Shake Shack, Fitbit or Facebook, this might be the way you do it—by putting shares of your firm up for public sale, sometimes in splashy fashion, complete with ticker tape and balloon drops.

In an IPO, a company’s stock typically gets listed on an established stock exchange. Large firms are listed on the NYSE or NASDAQ, while small and medium-size companies are traded on other exchanges.

Kaya Shack is traded on the OTCQB, an exchange for entrepreneurial and development-stage U.S. and international companies. “The exchange you wind up on is a function of your size, compliance level, stage of revenues,” Frank says. “Theoretically we could move up to a more advanced, more prestigious exchange, but that would happen when we meet the criteria.”

After the IPO is complete, a company is required to file financial annual and quarterly statements with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The SEC makes these financial statements available to the public via its Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis and Retrieval (EDGAR) database.

Varying transparency and disclosure levels are associated with different corporate structures. Certain types of public companies don’t need to be fully reported, depending on the degree to which they elect to be public. (More on this later.)

The Kaya Shack Route

Like many small companies, Kaya Shack went public via a “reverse merger.” It is a different path to the same end: A company whose stock can be purchased, traded and sold by the investing public.

A reverse merger involves an already- public company acquiring a private company, and that private company assuming control of the merged firm.

Kaya Shack’s corporate lineage leads to former parent company and biofuel startup Alternative Fuels America Inc. (AFAI). In January 2014, AFAI entered the legal marijuana business, and in February this year announced it would cease biofuels activities to focus on cannabis.

That direction change came after AFAI leaders, including Frank, had been searching for ways to supplement the growth of the firm’s biofuel crop. They noted burgeoning state governments’ support for regulated medical and recreational cannabis. “This idea of marijuana kept popping up,” Frank recalls. “We started to look at where we might be able to [grow]—not necessarily instead of our [existing biofuels operation], but alongside. And as sometimes happens, the tail starts wagging the dog. The board said, ‘This is where the real opportunity is.’”

AFAI changed its name to Kaya Holdings and its ticker symbol to KAYS on April 7 to reflect the company’s focus on legal cannabis. The Fort Lauderdale, Fla.-based firm now has a corporate staff of three, two board members, retail employees who operate the flagship dispensary and seven full-time employees working at the Southeast Portland cultivation site, with additional staff hired during harvest/trimming.

Public vs. Private Tradeoffs: The Upsides

There are three major upsides to being a public firm, says Frank, based on his experience with AFAI and Kaya Holdings. “You have access to markets and capital you wouldn’t have as a private company,” he notes. “You have the currency of your shares to utilize in doing certain kinds of transactions. I could theoretically compensate staff with not only dollars but stock.”

Indeed, Kaya Shack employees who work in a store more than six months receive a stock award.

Finally, a public company has liquidity a private company does not. If an individual wanted to invest $1,000 into a private dispensary, but then needed the money back six months later, no mechanism exists to easily retrieve it. “Provided you’ve created sufficient interest and market in the shares, a public company is able to allow that person to … take their money back,” Frank says, by selling their shares.

Public vs. Private Tradeoffs: The Not-So-Upsides

Those upsides come with costs, naturally. The most burdensome and challenging is the cost of regulatory compliance, since there is no difference in what the law expects from Kaya Holdings and much bigger players such as McDonald’s, Starbucks or Home Depot.

“The scope of their work is much greater, so they’re paying a lot more money to their lawyers and accountants, but the requirements are no different,” he says of the larger public companies. “Sometimes those requirements are burdensome to a company of our size and our stage of development. But it’s a classic dilemma—there’s a rule you have to follow, so you follow it.”

A significant component of public- company compliance is audits. Frank stresses that a company’s accountants—who will shepherd audits thorough the regulatory process—should set up a firm’s books knowing they will be audited.

“Smaller companies tend not to be as focused on filing; at the beginning of the day, when we think about all the things we need to do, [it’s not on the list]. Organizing the first [AFAI] audit was a nightmare because we hadn’t set everything up with the audit in mind.”

Companies also need to consider stringent rules regarding communication once a firm is public. Disclosure of information that may affect investors’ perception of the company takes on an entirely new meaning: “What I can say, what I can’t,” Frank says. “That’s one of the things you have to be careful about.”

The flip side of tighter-lipped operations is what Frank summarizes as “the need for thick skin.”

“As a public company ... you’re completely transparent, so everybody knows your numbers, what you’re earning, where the money goes,” he says. “You announce your company’s intentions, and you’re judged [on your execution of those plans]. ... But you’re dealing with investors using your public status as a tool for them to make short-term money. Those people don’t have the company’s interest at heart,” he adds. “Sometimes it’s very frustrating, because you’re trying to execute on a long-term plan, and ... you still have to operate your business. It’s a whole separate set of battles that as a private company you weren’t even thinking about.”

Overall, Frank notes, the best thing a potential IPO-seeker can do is a thorough analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of being public, particularly in an industry in which there is already a heavy compliance burden.

“Think about whether there’s that second level of compliance you’re built for,” he says. “Now we’re not that burdened, because we figured it out. It took the better part of two years. There are efficiencies, and setting yourself up to meet them from the beginning makes it so much easier. But understand that it really is a relinquishing of certain controls; you have to be comfortable with that. A small business owner has a lot of leeway that he or she won’t have in a public environment.”

Other IPO Options

Beyond the reverse merger Kaya Shack utilized to go public, several other means can accomplish the same end. Small firms can accumulate a sufficient number of shareholders to permit them to register with the SEC. Or (though this is normally a tactic used by larger firms), any company can pursue a traditional IPO, in which it will typically partner with an underwriter—an investment bank that manages and sells the IPO on behalf of the company.

Underwriters obtain prospective investors’ “indications of interest” before the IPO date and use this interest to recommend a share price. The two parties determine the IPO’s total share price, taking into account prospective orders for shares, market conditions, analysis and, of course, negotiation (since the underwriter’s compensation is typically a percentage of the IPO). The higher the price, the more capital the company raises in its offering.

Legal Concerns

As in any economic sector, some market players will look to prey on unwary investors. The SEC and the non-governmental Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, or FINRA, have warned investors to use caution when considering marijuana investments, as cannabis companies are vulnerable to federal prosecution as long as marijuana remains a Schedule I (and therefore illegal) drug under the Drug Enforcement Agency’s Controlled Substance Act.

The SEC’s Office of Investor Education and Advocacy in May 2014 suspended trading of five listed marijuana-related companies: FusionPharm, Cannabusiness Group, GrowLife, Advanced Cannabis Solutions, and Petrotech Oil and Gas. It explained in a statement that questions had arisen about “the accuracy of publicly available information about these companies’ operations. For two of the companies, the trading suspensions were also based on potential illegal activity (unlawful sales of securities and market manipulation).”

Frank notes that Kaya Shack received a call from FINRA in the process of going public. “They had some questions about what we were planning. They wanted to make sure we weren’t engaging in PR fluff,” he says.

While the regulators were helpful, Frank stresses that would-be public companies should never expect the SEC and FINRA to provide guidance or a helping hand. “The SEC regulates across the board. The fact that we’re a cannabis company doesn’t mean a thing to them,” he says. “You better have good lawyers. That’s not because it’s marijuana, it’s because it’s public. There’s no, ‘Oops, I didn’t know.’”

Expanding Operations

While Kaya Shack currently operates only on the medical side, the company plans to move into recreational sales this fall. Oregon residents last year approved a resolution to make recreational marijuana legal and available statewide, opening the door for the expansion.

Kaya Shack also is working to open additional dispensaries in Oregon: A second location was, at press time, on track to open by mid-October, when recreational sales were slated to begin, and a third locations was slated to be up and running by the end of October.

The company initially had set its scope even wider, envisioning a chain of safe, reputable dispensaries around the country. The uneven regulatory and legal landscape forced it to scale back those ambitions in the short term.

“Looking at this industry from a national perspective, part of the problem is the variance from one state to the other, and even within states, some allowing certain things, some not,” Frank notes. “It’s tough to get a handle on it. What we learned very quickly was that it isn’t wise to run too far ahead of the regulations. We had planned to open four to six stores, but said, ‘Wait a minute, we don’t want to build stores only to find that they’re zoned out or burdened with different kinds of compliance.’”

He says Kaya Shack frequently looks to its local attorneys, including two in Oregon, because bulletproof compliance is critical in the nascent age of legal marijuana. “The industry’s future relies on what all the players in the industry do,” he stresses. “If we show ourselves as unable to be compliant, the rest of the states won’t come on board.”