Whenever people call Colorado the first state to legalize cannabis, Leif and Arthur Abel, co-founders of medical-grade marijuana producer Greatland Ganja, can’t help but be amused.

“It always put a smile on my face when people talked about Colorado being the first one in the country, because everybody seems to have forgotten the '70s,” says Arthur, 36. He is the manager at Alaska-based Greatland Ganja and oversees the day-to-day operations of the facility and greenhouses.

While most think cannabis was legal in the United States until the early 20th century, when multiple acts of Congress outlawed the plant, Alaska only truly criminalized the plant in 1991. Prior to that, the state recognized a constitutional right to privacy in using cannabis in your own home thanks to a landmark Alaskan Supreme Court case in 1975: Ravin v. State. That’s when the Abel patriarch, Robert Seymour Abel, made his way to the northernmost state, eventually building a life and a family there.

Growing up on the Yukon River in interior Alaska, the brothers lived what could be called a “subsistence-based lifestyle,” where days were spent fishing, hunting, trapping and, most relevantly, gardening. Living in a remote location also meant the Abel family needed to find their own solutions to medical problems, and cannabis was a big part of their lives.

Photos courtesy of Chevelle Abel

“From our perspective growing up out there, it wasn't really too much different than any number of other plants that they were growing, except for we didn't consume the cannabis,” Arthur says. “That was just for Mom and Dad.”

Only during infrequent trips into town did the brothers realize how bold their family was in growing cannabis.

“Going through the whole realization that a plant that my dad is growing could get our parents taken away … as a kid, when you finally have that realization, it's pretty darn scary,” says Leif, 39. He is the company’s head of compliance and works closely with the state to ensure Greatland Ganja is compliant with regulations.

As scary as having your parents taken away is, that nerve is what allowed Greatland Ganja to get off to a running start.

Fortuna Audaces Iuvat

The Latin phrase translates to "Fortune favors the bold," and few were bolder than the Abel family when it came to setting up their cultivation business.

Medical marijuana has been legal in the state of Alaska since 1998, but commercial sales of medical marijuana were never allowed. Instead, a caregiver system was implemented. Primary caregivers are limited to one patient, unless the caregiver was “simultaneously caring for two or more patients who are related to the caregiver by at least the fourth degree of kinship by blood or marriage,” according to Alaska’s medical cannabis statutes. This remains the status of medical cannabis in the state to this day.

It was a call from their father in 2013 about what was happening in Colorado (with legalization) that turned the brothers on to the possibility of making a living from cannabis. Alaska had its own ballot initiative collecting signatures at the time, and the brothers wasted no time in getting ready.

“We talked some about the initiative here, and he [Robert] suggested that we start a family business in this vein, and we started business planning at that point,” Leif recalls. “We started writing a business plan basically that January that Colorado came online [2014].”

In another bold move, the Abel family began constructing their indoor facility and greenhouses in the fall of 2015, before regulations were even official or created. Trusses for the indoor facility were being put up before the state even drafted facility design regulations.

“A lot of the cultivators were much slower to come online than we were because they started their planning maybe a little bit later,” Leif says. “A lot of it had to do, I think, though, with the risk involved.”

The risks with building a facility before regulations are drafted are obvious: You could build a huge facility with room for expansion, only to see regulators limit canopy size; your facility might not be up to state or even municipal code; your facility’s security might not be up to par. … The potential pitfalls are many.

By being proactive and working with officials in shaping the state’s cannabis regulations, however, Leif was able to manage and limit those risks. Although not without some close calls. When the state was thinking about changing security fencing requirements, Leif weighed in on the issue.

“I was on the phone testifying to the Marijuana Control Board that they should not increase the fence height around [a] site, that they should leave it at 6 feet instead of [moving] it to 8 [feet], while we were in the process of building a very expensive 6-foot-tall fence,” he says with a laugh.

Despite the doubts he had about taking those risks, taking them is what allowed Greatland Ganja to become the second licensed producer in the state of Alaska, and the first to bring a product to market.

And, in the end, the Marijuana Control Board settled on a 6-foot fence.

Photos courtesy of Chevelle Abel

Farmers at Heart

If you looked behind that 6-foot fence, you would find something that few other Alaskan cannabis growers have: a farming tractor. That’s because the Abel family members are farmers at heart (and, as the brothers put it, “because soil is heavy”). That’s the approach they took to growing cannabis, electing to grow in greenhouses and planting their crops in the ground.

“We planted it like we plant kale at home,” states Leif. “Literally in beds in the ground, and we love growing that way.”

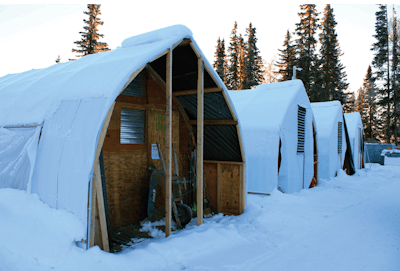

The “Gnome Domes,” as they are called on the farm after an employee coined the term, consist of four 12-foot-wide greenhouses of varying length, totaling up to 4,800 square feet of canopy. They were completely designed and built by the co-founders, who also run their own contracting company.

“We bought electrical conduit and a tubing bender and manufactured all the pieces … and then tack-welded the whole thing together,” Arthur says. While self-constructing is not for everyone, he says building the greenhouses themselves instead of ordering pre-fabricated ones from a manufacturer from the continental U.S. cut their building expenses by 75 percent or more.

“Getting materials up here is a huge challenge for us and a huge cost. Alaska's just a hard place to get things to,” he explains. This translates into the greenhouses being fairly low-tech. Except for a fan system, most of the work in the greenhouses is done by hand, including rolling the blackout screens up and down. The absence of a heating system and supplemental lighting (at least any permanent ones) also means the greenhouses are currently limited to one crop a year.

But that isn’t to say Alaska doesn’t have its benefits.

Instead of ordering equipment or nutrients from out-of-state vendors, the Abels locally source everything they can. With the state’s massive fish industry, the products are bountiful: clam flour, crab meal, shrimp meal, fish and fish bone meal are all available from local vendors selling local products. Even the worm castings are bought from a local worm farm, Grandpa's Worm Castings.

Arthur says buying local products has other benefits outside of supporting the local economy and keeping costs down.

“It's real interesting that it works out that those are … organic nutrients … that are locally sourced, so it really fits well with what we're trying to do in the nutrient regard,” he says. For the Abels, the same principle applies to growing organic-level cannabis as it does to the organic food they grow for their own tables: If they wouldn’t let their families use it, they wouldn’t sell it to anyone else.

Cultivation in the Alaskan Environment

In those darker months (which make up most of the year in The Last Frontier), production is focused in Greatland Ganja's hydroponic grow rooms located in their warehouse on the same property.

Going from growing outdoors using organic practices and products to an indoor, hydroponic setup might seem a large shift in practices, but it’s key for them to continue growing consistent, quality cannabis.

“There's way less variances in nutrients and supplies that you get when you're buying the chemical fertilizers or standard fertilizers,” Arthur says. “They are pretty much the same every time, so it's something that we're real comfortable with, that we can get a maximum yield with those hydroponics.”

Their indoor facility spans roughly 2,300 square feet, with half of that being allocated to office and garage/general use space. This leaves over 1,100 square feet of grow space. A flowering room of 500 square feet makes up most of that.

While their lighting system might sound simple (16 1,000-watt single-headed HPS lights interspersed with T5s), Greatland Ganja added their own twist to it: hoists.

“Stationary lights are one of the things that always make me crack a smile,” Arthur says. “I know somebody that was literally putting bricks underneath each plant and then removing them as the plant got taller and moving the plant down,” he continues with a chuckle.

“I ordered a $100 mechanical hoist off of Amazon and threw it on these lights. … When [the plants are] small, I drop the light down close. The plants grow, and every other day, you inch it up a little bit. You're going to get maximum growth the entire time that way, and prevent burning.”

Letting air systems run unsupervised is another issue Alaska growers need to keep in mind.

“In the wintertime, we've got such a good air system that we could actually freeze all of our plants,” explains Arthur. He says the outside air is so cold and the system so efficient in exchanging air that the system can’t bring the outside air up to the right temperature before it’s blown into the flowering rooms.

An air system of that quality is needed in the summer, when it can reach upwards of 80 degrees [Fahrenheit] outside and you need an air system that can circulate the entire room’s air in 2 minutes. But in the winter, “if you had it on the same setting, and it blew all that cold air in there … you could actually wilt the whole room of plants by not having that set correctly,” he says.

But having those air temperature differentials can be a blessing if you know how to channel them. Arthur says they save money on air conditioning in the winter. All they need to do, he says, is make more adjustments to their systems. But the brothers aren’t complaining. “Maintaining an indoor environment is complex in any place,” Arthur says.

But the plan for Greatland Ganja is to not to expand the indoor grow, but rather build more greenhouses. The brothers plan on slowly increasing the number of greenhouses they have every year until they reach a greenhouse canopy size of roughly 25,000 square feet.

“Our focus is organically growing in the greenhouses as much as possible, and a small hydroponic outfit to ... keep us through the winter and to maintain our mothers,” Arthur says.

Photos courtesy of Chevelle Abel

Great Brands Last

Marketing can be hard to do right and can be a frustrating and time-consuming process, but the Abels understand its importance and made it a priority from the get-go. “Right when we started business planning, we started branding the company because we knew branding was going to be important, along with a quality product,” says Leif.

Everything that can be branded by Greatland Ganja is branded — from an apparel line, to branded flower, pre-rolls, full-service delivery (with budtender training included) and very important co-branding partnerships with local extractors and processors (including with the first state-licensed extraction and edibles company, Frozen Budz). The Abels try to make sure the end user knows what they’re getting and who they’re getting it from. Labeling plays a big part in achieving that.

“We want the consumer to … be able to get a hold of us with any questions, whether they be compliments, concerns, suggestions or just the story of how it helps them,” Leif says.

Even the packaging their product goes in is used as a branding tool. Glass jars are used to display and sell Greatland Ganja’s hang-dried, hand-trimmed premium flower. Standard plastic packaging is kept for its “everyday” quality flower, which is mostly machine trimmed using a T4 Twister by Keirton. (Although according to the brothers, most people think the machine-trimmed flower is hand-trimmed.)

Surprisingly, all of their branding work over the last three years has cost them less than $20,000. A lot of that has to do with the brothers’ use of “situational branding,” where their brand gets publicity through indirect channels.

“So because we were vocal in the rule-making process, a lot of people got to know our name, and it was mostly in a positive way,” Leif says. “A lot of it had to do with just grass-roots organizing and getting our name out there in the state as somebody that's willing to put ourselves forth as people from the cannabis culture, and willing to stand up for it.”

Leif is the more vocal one of the duo. He is a founding member of the Alaska Marijuana Industry Association, worked with the Marijuana Policy Project (MPP) on getting the state’s voter initiative passed, and has been active in the media by writing public comments in local and national publications. After battling against a commercial marijuana opt-out move by a local assemblyman in the Kenai Peninsula Borough of Kasilof, where their cultivation site is located, Leif was appointed chair of the marijuana task force by the mayor. Greatland Ganja now is currently fighting against a voter initiative to opt-out that is scheduled for this October.

“We drew a lot of media attention because we were willing to be vocal and willing to talk about what we were planning to do long before a lot of other people were,” he says. “And we tried to use that in a positive way to both positively highlight the cannabis culture and to brand somewhat for future business.”

The Greatland Ganja co-founders understand that branding will make or break companies in the future. And that goes double for Alaskan growers who are looking to both thrive in-state and expand into other markets. “With our high cost to produce up here, if we don't want lower-cost products to take over our market … and if we want to … expand into other markets in the states, the only way we're going to pull that off is by having a high-quality product and a recognizable brand,” says Arthur.

Embracing the Wilderness

Great quality cannabis, farm-to-table-like growing and branding is what has allowed Greatland Ganja to set itself up as a model of success in the crowded Alaska cannabis industry. Despite the fact that growers outnumber retailers by a wide margin in the state, it is still a seller’s market. According to the brothers, that’s partly because most license holders are what the state classifies as “limited cultivators,” or mom-and-pop businesses with a canopy under 500 square feet.

Unlike in other states that legalized adult-use marijuana after having a robust medical market, Alaska’s caregiver system for its medical marijuana program also left a lot of growers unprepared to supply such a large demand. “We went from 0 to 100 here,” Leif says.

So, would they recommend people move to Alaska and start growing cannabis to fill the gaps in production? “Don't do it. It's too hard,” Arthur says with a hearty laugh.

But he’s not wrong. Before opening a cannabis business, the license applicant must be a resident of the state until they are eligible for the state’s permanent fund dividend, which requires that a person be a resident of Alaska for a full calendar year and not claim residency in another state or country, among other requirements.

There are workarounds to that, with partnering with locals being the main one. The drawback there: Your name can’t appear on the license.

Like other markets, Alaska has unique challenges: from increased utility costs to marked-up prices on out-of-state materials and higher transportation costs. Although shared by most other growers across the world, those issues can seem magnified by the remoteness of the Alaskan wilderness.

“Even if you have a really good background cultivating in Washington or Colorado or Oregon, or any number of the other states, I would say expect a lot of unforeseen hurdles when you get here,” Arthur cautions.

With all the challenges they’ve faced, are facing and will face, would the brothers have it any other way? Not a chance. “Since I was a kid, I dreamed about having a family business,” Leif says. “… This is exactly what I want to be doing.”