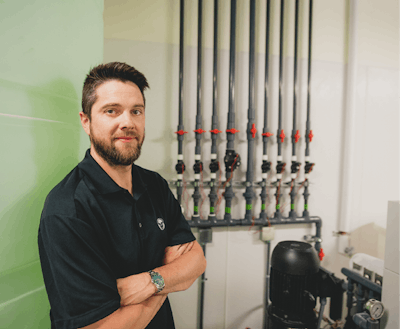

As the (de)construction crew bangs away behind him, taking down walls with sledgehammers and setting up new ones for his work-in-progress dispensary, Scott Reach looks at his new 54,000-square-foot Denver growing facility and cannot help but feel a sense of surreality.

“Two years ago, this was just a conversation around a table,” remembers Reach, the founder and COO of RD Industries, Rare Dankness’ umbrella company. “I pitched this grand scheme to a few of my friends, and they were like, ‘Yeah dude, no one is going to lend you that money for that,’” he continues with a chuckle.

But this is a dream come true for Reach, a culmination of consulting on more than 300 grows over the last five years and countless more before that. It’s an achievement he ranks up there with breeding one of his signature strains, Ghost Train Haze.

Like many others in the industry, Reach ended up where he is almost by accident. An Alabama-born bike mechanic with a degree in welding and metallurgy, he made his name in the cannabis industry as one of the main members of the Devil’s Harvest Krew (DHK), the storied cannabis-trading group. It is from that trade and hard work that Reach, also known as Moonshine in his DHK days, was able to create and popularize some of cannabis’ most popular and potent strains.

Today, Rare Dankness is already one of the most recognized brands in cannabis, with Rare Dankness strains being grown and traded worldwide thanks to its international seed banks. And while Reach has gone to great lengths to cultivate it, how the brand name came to be was quite serendipitous.

In 2009, when Reach had his Longmont, Colo., medical dispensary, called Stone Mountain (he sold it after realizing how much more complicated a dispensary was compared to a growing operation, he says), a regular customer, “this guy who lived up in the mountains,” Reach describes, came into the store one day excited about his next seed purchase.

“If you're not on the technology side of cannabis, you're just going to be on the farming side, and there's not a lot of money on the farming side.” — Scott Reach

Reach remembers it clearly. “He was just like, ‘Man … it’s really rare to see this type of dankness anywhere in the state.’ ”

Reach and his only employee had a lightbulb moment.

“We were both like, ‘Rare Dankness — that’s a cool name for a strain or a seed company or whatever.’ ” Officially founded in 2009, Rare Dankness has grown to be a worldwide seed bank, with many of the company’s original strains winning major honors, including numerous Cannabis Cup awards.

With this new Denver facility, Reach wants to extend RD Industries and Rare Dankness’ status as a provider of consistently high-quality cannabis products from coast to coast.

“I just want to be known for … [having] the exact same product no matter where you’re going. I want to control what our buds look like, how that cure is handled, the oil, everything.”

And he’s not keeping any secrets as to how he plans to do it.

High Tech, High Quality

When visiting other dispensaries and growing operations, Reach says he sees too many workers “doing very menial tasks that you can easily automate.”

That’s why he went out of his way to bring as much technology as he could into the new Denver operation. “We want to start looking at this plant really differently so that we can … create a more structured and standardized product as we go forward,” he says.

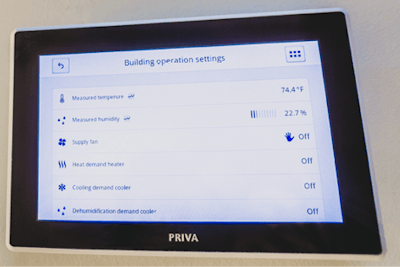

One of the most significant technologies RD Industries brought in to the facility was a Priva control and automation system.

Priva is one of the few high-end, commercial-horticulture-system companies that has done business with cannabis businesses, Reach says. (It also designed a system for Tweed’s facility in Smiths Falls, Ontario, he says.) And yet it is still a relative unknown to many in this industry. Reach first encountered its systems during a trip to Disney World, which uses Priva’s horticulture systems. After doing his homework, he wasted no time in contacting the company.

“Typically when people are talking about Priva, they’re talking about clean rooms, industrial-level stuff,” he says.

Reach says the Priva system has given him, in addition to a clean room system, better control over his grow-space, from managing irrigation times to humidifying and dehumidifying, and from adjusting temperature to lighting, the latter being one of the facility’s key features.

“They turn the lights on in such a way that there’s a slight pause in between each light cycling on throughout, no matter what size room you’re lighting, so that you never get those crazy spikes in your electricity bill,” Reach says, adding that, “in Colorado, … they base our entire bill off of … those energy spikes.”

The new facility also will be extremely efficient in its water consumption, according to Reach. Graywater will be reused after passing through a UV water filtration system with peroxide injection. As the collected graywater goes through the system, special lamps emitting a UV ray at a specific frequency will destroy any microorganisms that could endanger a crop, “so every bit of irrigation runoff, every bit of dehumidification and condensation that’s built up on the fan coils, is recaptured and sterilized, and spit back into the irrigation system,” Reach explains.

But all that technology going in to maintaining and protecting his harvest is of no use if he can’t control human error. Which is why Reach went a step further in security and access, giving all his growers and employees key fobs and restricting access to where each employee needs to be.

“Each quadrant is its own grow space, so to speak. So the team that is working at the bench floor, they only go on the bench floor. … Their fobs won’t allow them to enter the flower room,” Reach says, “which is important for … overall pest management and cross-contamination within the facilities.”

If there were any more measures he could have put into this high-tech operation, he would have.

“Honestly, if I could have had the little eyeball somewhere in each room so when I walked in, the thing is like, ‘Good morning, Mr. Reach,’ I would have done that. But no one’s doing that,” he says with a laugh.

Reach would like to see his highly-controlled and automated facility produce 15,000 pounds of high-quality product when it is fully operational. He’s taking measures to ensure that his customers see that quality by having only the top 30 percent of the buds sold as flower, with the rest of the plant being stripped and turned into concentrate.

This business move not only allows him to make sure customers get the best buds, but also will allow him to market his concentrates as what he calls “whole-plant extract,” because the plant hasn’t been completely stripped during the defoliation process.

High Tech, High Price

Reach’s friends weren’t entirely wrong when they told him he would not be able to find someone willing to put the money down for him to turn his vision into a reality. He met with more than two dozen investment groups and individuals with a pitch that he describes as “let me borrow $10 million and get no equity.” Needless to say, that was a tough pill to swallow.

And while most of those investors were interested in his project, what they were asking for in return was too steep a price for Reach (steep interest rates and/or equity). He even lost his temper during one of those meetings when a potential investor made an offer with particularly ludicrous conditions, which he says is not uncommon in the industry.

The industry may be a victim of its own success, as booming business attracts what Reach says are “people looking to make a quick buck,” who don’t actually care about the industry and are looking to take advantage of less business-savvy growers.

“We just call it the ‘weed tax,’” he says. “Everywhere you go, in Colorado especially … if you don’t price it out and shop around … someone’s going to come to you with a weed tax added onto it.”

But in September 2014, Reach found someone willing to deal with him fairly and he walked away with a (fairly) low-interest (sub 10-percent) personal loan, while retaining 100-percent ownership of his company. Well, along with his wife Pamela.

In 2010, a battle with cancer changed Reach from being a grower and consumer “to actually really, really needing the plant,” he says. During this bout with cancer, Reach doubled down on his devotion to building a successful cannabis brand and seeing the plant legalized.

It was then that Pamela officially joined her husband’s company, realizing that day-to-day administrative matters needed a full-time person. She took over that role so that Reach could concentrate on growing and breeding.

“The difference that she brought to the company was just a little calmer head and better business sense, and a little more professionalism than your typical grower,” Reach says. “At this point, man, I’m just a pretty face,” he says with a chuckle. “The business is the way the business is because of her.”

Protecting Your Territory

In order to build his brand the way he wanted, Reach needed to control who he works with — which is why, he says, he turned his back on a lot of money and pulled all of his licensing contracts, including those with cannabis industry players RiverRock Cannabis and Green Man Cannabis, to license his genetics work to himself. This works because he has taken precautions to keep his companies separate.

“It maintains the integrity that we’ve built with the brand,” he explains.

He also needed to structure the company correctly. Under RD Industries is the new Colorado-based company that will operate the Denver grow facility and the dispensary, House of Dankness. Everything sold at House of Dankness will be sold using the Rare Dankness brand, which will be licensed by Reach’s genetics company, Rare Dankness.

Reach plans to use his network to stock certain dispensaries in Colorado. Just probably not too many Denver shops. “My plan is to sell 50 percent of [our product] out our front door. And then the other 50 percent I’ll wholesale out to a variety of places,” he says. “Not only does it benefit us to be able to send you to a different place in each city, so you don’t necessarily have to come to Denver, but it drives sales toward those businesses that we’re friendly with.”

Reach is not completely against stocking friendly Denver shops. But he also does not want to compete against himself, so some of his more “exclusive” strains, like Ghost Train Haze and Star Killer, will only be found at House of Dankness. Nothing personal, though.

“I spent 17 years in the bicycle industry; it’s just territory protection,” Reach says.

As for edibles, Reach wants nothing to do with making them. Instead, he has set up strategic partnerships with already-established edibles companies like Incredibles and Mary’s Medicinals, where he will provide Rare Dankness concentrates for them to work with.

“That way, we can always ensure that we’re putting material into it that’s not going to come back with a recall or any kind of pesticide issue or whatever,” Reach says. “If we’re really trying to create stuff for medical patients, they need to be able to get it [exactly the] same every single time to know whether or not it’s working for them.”

Spreading the Dankness

Even as the construction crew’s thuds and crashes echo in his ears, Reach is already looking 12 months ahead toward his next big project: a multi-acre, fully automated greenhouse grow. And if he gets his wish, the next Rare Dankness facility will not be in Colorado, but rather Nevada.

“Vegas — I really want Vegas to be our next hub,” Reach says eagerly. The only question mark for his plan is whether Nevada will legalize recreational cannabis. (A petition vote by Nevada residents will happen Nov. 8.) “Las Vegas has a huge tourist population. Those are the type of things, as a brand, that you have to capitalize on.”

That greenhouse, wherever it ultimately ends up being, will use the same technology and systems as the Denver facility, a move Reach planned from the start.

He sees his Denver facility as a training ground for the future, larger-scale greenhouses, where new employees can shadow growers and learn the systems and protocols (including the Priva system) before being sent out to their new location.

It’s a model he wants to replicate because, as he says, “if you’re not on the technology side of cannabis, you’re just going to be on the farming side, and there’s not a lot of money on the farming side.”

As the industry moves forward, the companies that find success and that will get attention from investors are going to be those who have invested heavily in facility design and automation, says Reach.

“In 2009, you could have gotten involved for less than $25,000, got a shop rolling and everything. Nowadays, it takes $3 million to $10 million in Colorado just to get rolling, $15 [million] to $25 [million] to actually compete with anything.”

That’s why Reach has invested so much in his facility: He hopes that while everyone else is playing catch-up to increasing industry standards, he can rest assured that Rare Dankness will always be one step ahead.