Where will you source the marijuana cultivars you intend to grow? Given that there are thousands of cultivars available today, with many more to come, do you know where they have come from and how you will utilize them? Many fail to recognize the importance of genetic diversity. However, genetic diversity is why not all seeds are created equal. Therefore, the clones, seeds and tissue cultures produced from different cultivars will vary.

So, where do the cultivars (genetics) of today come from?

Landraces: A landrace is defined as a traditional plant variety that has been selected by local farmers. Landraces were the basic foundations of the cultivars we know today. Today's growers utilize hybrids. Only a few grow Old World landraces because they typically require a longer maturation time and are less potent than hybrids; but there are some incredible growers, such as The Highest Grade, who are now growing and investigating the properties of these Old World gems. I expect to see a resurgence of boutique landrace production in the near future.

Hybrids: Hybrids result from crossing two different landraces, breeder's varieties or cultivars. Today, most hybrid cultivars are considered to be in the public domain. (More on that later.) Hybrids are what are predominantly grown today, along with landrace variants and pure-lineage Afghan cultivars.

Breeders (the short version): In the 1960s and 1970s, cannabis consumers and aficionados traveled the world. Many places they traveled were source countries for marijuana and hashish. These travelers noticed the unique characteristics and diversity of phenotypes compared to the imported marijuana to which they were accustomed. Many brought seeds home from places such as Afghanistan, Pakistan, Lebanon, Morocco, Nepal, Tibet and India, as well as grew seeds from imported Mexican, Colombian, Jamaican and Thai cannabis.Thus began the selection and breeding that produced the hybrid cannabis cultivars we know today, and that continue to be bred to produce the cultivars of tomorrow. Seed companies began breeding specialized seeds and offering them for public sale from Holland in the early 1980s. Thousands of cultivars have been bred since.

With the change in state cannabis laws, some seed companies have begun breeding and selling seeds here, as well. Today’s breeders have spent tens of thousands of dollars marketing their companies and genetics lines; hundreds of thousands more have been spent developing their breeding programs and producing the seeds they sell. But after being sold and in the hands of the public for 365 days, the hybrids are classified as “public domain,” meaning that just like the landraces, these seeds are considered public property that cannot be patented or protected. There has been no exclusivity.

But what does this really mean? It means a company can do anything it wants with public domain genetics. The cannabis world essentially can be a free-for-all with no acknowledgment nor financial reward given to the breeder.

Cultivars that are not in the public domain, are exclusive to the breeder and have unique characteristics are patentable from now on.

Without patent protections, it is not legally necessary to compensate breeders, so growers are left with a choice: do the right thing and form a licensing agreement with the breeder to produce his cultivar; or, use the breeder’s work without permission (and put the onus on the breeder to decide whether to try sue for compensation), in which case, you might as well steal anything you desire, rename it after your mom and call it your own.

The decisions a company makes from the start ultimately will earn or lose the consumer’s respect. By making ethical decisions, you ultimately will be recognized and respected.

A Patent That Could Change the Future

Recently, however, something happened that could significantly change the landscape for breeders. Vice magazine revealed that on Aug. 4, 2015, U.S. patent number 9095554 was granted for a cannabis cultivar that contains significant amounts of THC — the very first of its kind ever granted. Vice reported. "A spokesperson for the U.S. Patent and Trade Office confirmed that officials are now accepting and processing patent applications for individual varieties of cannabis, along with innovative medical uses for the plant and other associated inventions."

I spoke with a representative of the firm (Cooley LLC) that filed the patent, and it is as legitimate as any other plant patent.

The implications of this granted patent are many.

What is patentable and what is not? Cultivars that are not in the public domain, are exclusive to the breeder and have unique characteristics are patentable from now on, based on the precedent set by U.S. Patent 9095554. All existing genetics, be they landrace, hybrid or anything else available to the public, are not.

So how will all this be sussed out and enforced? No one really knows. The only thing certain is it will be a huge legal battle, many times over. A lot of money will be spent on lawyers, for both enforcement and defense.

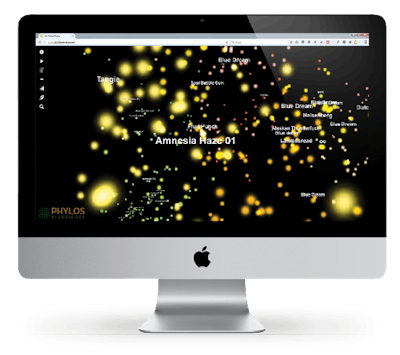

How will it be proven that a given cultivar existed in the public domain? Recently formed groups are dealing with this issue and many other genetics-related subjects, such as the Agricultural Genomics Foundation of Colorado, which is working on mapping DNA and marker identification. The Open Cannabis Project (OCP) is collecting cannabis DNA samples to publish in a massive database to determine if a given cultivar was available to the public before or after it was patented. In conjunction with Phylos Bioscience, OCP is offering an incredible, 3-D, interactive online guide that visually portrays the genetic relationships of almost 1,000 cannabis samples using genetic data (Galaxy.Phylosbioscience.com).

Before you source your genetics you need to consider a few more things.

- Will you start from propagated clones?

- Where will you obtain them?

- Will they be the most desirable representation of a given cultivar?

- Are they free of pests and diseases?

Or will you start from seeds? If so:

- Where will you obtain them?

- How many seeds must you germinate, cultivate, mature and bring to flower to get the most desirable representation of that cultivar, which includes the labor and time-intensive process of eliminating male plants? (It is now possible to determine sex by genetic analysis.)

All of this takes a lot of time and funding, especially if you intend on cultivating many different cultivars. And once again, you are faced with those crucial questions:

- From whom will you source?

- To whom will you pay royalties or licensing fees?

- Will you just jump into that aforementioned free-for-all?

Seed breeders from this point on will need to retain some form of exclusivity for the genetics they develop, meaning patenting and licensing, which, in turn, means a cultivator and a retailer can legally associate their branded products with the appropriate breeder. It's all about to get very complicated.

But legalization will bring advancements, too, such as tissue culture, and cellular division and replication (not genetic modification), which will allow for the production of millions of like specimens that are all-female, sterile in that there are no bugs or disease infestations, and are perfect examples of a given cultivar. These plants will be patented, branded and will come with exclusive licensing agreements and contracts for royalties, which again leads to exclusivity.

There will always be public domain genetics and those that breeders choose to keep public in the future. In the end, however, either the cannabis industry protects itself and the intellectual property (IP) it has pioneered and created, or the newly emerging corporate entities will do so.

The cultivars you grow are also to some degree dictated by available space, the intended growth method, and the environment you choose. Indoor or greenhouse production can each accommodate various growth methods. Will you grow small, medium or large plants? Will you train/spread out (aka screen-of-green) the plants? Use large containers? Small containers? Grow in the ground?

Many of the landraces mentioned earlier are referred to as sativas — narrow-leaflet cultivars. These typically take longer to mature and require a longer flowering period. They can be a challenge to cultivate indoors en masse due to their size. They also have a higher cost of production because of these traits. But traditional pre-Afghan cultivars are now being re-investigated — greenhouses are perfect for cultivating them, as are market conditions and many growers’ desire to provide more diverse offerings. And growers will explore further what beneficial properties these cultivars have and which can be utilized in future breeding programs, ultimately resulting in thousands of new cultivars in the future.

To some extent, genetic diversity and varying maturation times also will dictate what method and environment you choose, in that it is labor-intensive to grow cultivars that mature and finish at very different rates. Whenever possible, try to grow plants that mature and finish at approximately the same time.

The Ever-Present Fear

Many in the cannabis industry fear corporate takeover of cannabis genetics. They fear monopolization and the legal avenues available to biotech corporations and others, such as tobacco companies. Again to quote the Vice article, “When contacted, Monsanto claims it has no interest in cannabis production or cannabis seed production. A tobacco representative stated that they also have no interest. But that does not mean they won't be if federal restrictions are ever lifted.”

I recently had a conversation with someone (who prefers to remain anonymous) who was asked to attend meetings with representatives and/or ex-employees of global agribusiness Syngenta Corp. (He was unclear on who all the attendees were.) The impression this person was left with was that Syngenta was definitely investigating the genetics of the cannabis plant.

And pharmaceutical interests are already being put to action.

Hortapharm B.V. was founded in 1990 in the Netherlands by David Watson, and together with David Pate and Rob Clarke, they obtained the first license issued by the Dutch government to open a cannabis research facility. Hortapharm pioneered the concept of breeding plants to produce single compounds and licensed varieties to GW Pharmaceuticals for the manufacture of pharmaceuticals. Hortapharm created cultivars that produce virtually single cannabinoids, approximately 98-percent THC or CBD relative to the total of other cannabinoids present.

Keeping in mind that research officially began in 1990, 26 years ago, it amazes me how fast everything cannabis-related is about to accelerate globally. Therefore, when cannabis is rescheduled and if federal restrictions are ever lifted, the legal realm of cannabis will quickly become very murky and very profitable for attorneys. And it will become very expensive to protect your IP.