Editor’s note: Throughout this story, the word “cannabis” is used in two different forms to mean two different things. The word “Cannabis” (italicized) is a taxonomic term used to denote Cannabis plants and crops composed of those plants. The word ”cannabis” (not italicized) is an adjective used to modify nouns, such as ”cannabis products,” ”cannabis activists” and ”cannabis legislation.”

Today, most people think they know what “hemp” is. They will point out that it has become everything from textiles, paper and building materials to foods, CBD oil and medicines.

Depending on set and setting, their perceptions can be both right and wrong, and sometimes even misleading. “Hemp” as an English term has equivalents in many languages, all originally denoting fiber products derived from the Cannabis plant. It comes from the Old English word henep and is of Germanic origin, related to both Dutch hennep and German hanf.

The primary definition of “hemp” in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary describes an Asian herb cultivated for its fiber and seed, as well as the fiber itself, and lastly as marijuana and hashish. British use of “hemp” is more encompassing, and the Oxford English Dictionary defines “hemp” as a term for the Cannabis plant especially when grown for fiber, as well as a name for other fiber plants, and as a term for “drug cannabis,” such as Indian hemp or hemp drugs.

In Europe, psychoactive Cannabis varieties were not traditionally associated with “hemp” medicines, which historically were derived only from hemp fibers and seeds. The fibers were considered to relieve pain and heal wounds, and the seeds also had healing effects. As historians, we’re opposed to mixing traditional terms with modern ones because they may no longer be correctly used.

Still, we need terms for everything, and those associated with products of the Cannabis plant continue to change as they gain new and different meanings. Maltese physician and educator Edward de Bono (1933-2021) summarized this predicament: “In a sense, words are encyclopedias of ignorance because they freeze perceptions at one moment in history and then insist we continue to use these frozen perceptions when we should be doing better.”

Early Definition of Hemp

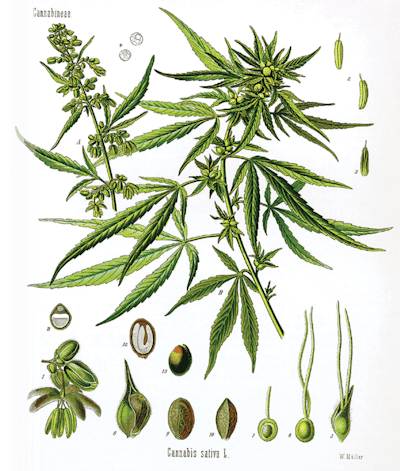

Many learned people have contributed to ordering our perceptions of nature. One of these was Swedish botanist Carl von Linné (also known as Carl Linnaeus), who in the 18th century established an international system based on Greek and Latin root words to name all organisms with unique terms that reflected their commonalities and could be understood across all languages. In the 1753 edition of the book Species Plantarum, von Linné included the binomial Cannabis sativa, meaning cultivated Cannabis.

Early taxonomists were initially compelled to classify plants growing within their regions, and hemp was a familiar fiber and seed crop throughout Europe. During von Linné’s lifetime, no explanation was needed about hemp’s uses or how it grew; people primarily grew it for its fibers. He even said “hemp” could also be made from other plants. By this time, “hemp” had already become a collective term for similar fiber plants and remains so today, such as Manila hemp and sisal hemp. Cannabis became known as “true hemp” to distinguish it from other fiber plants.

Before the Industrial Revolution, almost every household, from simple subsistence farms to the noble mansions of Europe, Russia, Anatolia, and the New World, cultivated European Cannabis sativa, often in small plots near their homes. The primary use of the fiber was for clothing and household textiles, sacking and cordage. Hemp fiber and fabrics also gained ritual significance in traditional cultures and still today are considered to possess purifying, protective and healing powers. Although the seeds were primarily used to sow the following year’s fiber crop, they were also a source of food, animal feed and medicine, as well as oil for many uses ranging from lamp oil to soaps.

A Change in Perception

Europe’s Cannabis was characterized as a common garden plant lacking any psychoactive potential. Asia’s Cannabis also produced both fiber and seeds, but in addition, it was used as a drug plant. This presented a distinct point of difference from European Cannabis.

When East Indian Cannabis arrived in Europe during the 18th century, it soon became recognized for its psychoactive effects. The French botanist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829) noted the obvious physical similarities with familiar European Cannabis, as well as its profound differences. In 1785, he gave the Indian varieties the unique species name Cannabis indica, meaning “Cannabis from India.” That definition drew the initial taxonomic boundary between hemp and drug Cannabis, the validity of which remains a topic of debate today.

Active ingredients derived from C. indica became increasingly important during the 19th century Victorian era, when the plant was used medicinally as well as for its psychoactive effects. Despite the centuries-long and widespread cultivation of European hemp for fiber and seed, those traditional uses shared by Asian cultures were of no immediate interest when Lamarck described the values of C. indica.

By the end of the 20th century, the European definition of “hemp” had taken on a more commercial orientation and came to describe Cannabis cultivars grown to produce stalks, fibers or seeds that were characterized by THC content below 0.3%.

Today’s concept of industrial hemp crosses regulatory boundaries between traditional hemp and drug cannabis. In the U.S., according to the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (the 2018 Farm Bill), any Cannabis containing less than 0.3% THC is legally classified as industrial hemp regardless of its end use. “Hemp” is therefore used to denote the plant as a source of not only fiber and seeds but also non-THC cannabinoids, such as CBD.

Modern-Day Definitions of Hemp

Today, hemp takes on various forms across the globe. In Europe and Asia, economically significant CBD yields of between 2% to 5% are extracted from the flowers of multi-product “industrial” hemp crops from which fiber and seed are also harvested. Across North America, CBD is largely extracted from drug cultivars that are much more closely related genetically to modern high-THC sinsemilla (seedless Cannabis) than they are to hemp fiber and seed cultivars.

Until recently, our Western perspectives for classifying the Cannabis plant were quite simplistic—cannabis drugs were illegal, and hemp fiber and seed were legal. As public knowledge grew, healthy utilitarian hemp fiber and seed products were considered good and therefore allowed, while drugs were considered bad and therefore proscribed. However, medicinal cannabis use straddles the fence. On one side, cannabis is now touted as a valuable medicine, while on the other side, it is still considered a dangerous drug of abuse. When CBD came along with all its purported health advantages and without any psychoactive baggage, an entirely new concept of “hemp” emerged.

So what, then, is hemp today? More recent legalistic definitions of “hemp” have extended its reach to include not only low-THC Cannabis plants, but also low-THC products derived from the plant, thereby stretching the definition far beyond traditional fiber and seed. This change was initially brought on by late 20th century European Union legislation redefining industrial “hemp” to represent all Cannabis plants and crops with low THC content. Since enactment of the 2018 Farm Bill, “hemp” has become nearly all-encompassing, while “cannabis” is used by some to refer only to marijuana, hashish and other drug products. Meanwhile, the taxonomic terms “sativa” and “indica” are commonly misused and have taken on slang connotations that confuse more than clarify. One mistake begets the next.

Until recently, the difference in appearance between hemp and drug cannabis crops was more obvious. Fiber and seed fields are densely sown, and the resulting crop is tightly spaced, which suppresses branching. Fiber crops are tall, often reaching 7 feet (2 meters) or more in height, while grain seed crops are usually less than 3 feet (1 meter) tall, but both are made up of both male and female plants with straight central stalks and few, if any, branches.

Cannabis can also be grown solely for its essential oil content by individually transplanting seedlings or cuttings farther apart to promote branching and increase flower yield. Although triple-cropping hemp fiber varieties for their stalks, seeds and essential oils is practiced in several countries, the vast majority of North American CBD is produced from drug varieties grown without seed. Modern CBD and other minor cannabinoid “hemp” cultivars are simply hybrid drug varieties with low THC content, rather than high-THC with only traces of minor cannabinoids, like most psychoactive sinsemilla varieties.

“Farm bill hemp” crops grown for CBD often look just like high-THC crops, making it difficult for regulators to determine the intent of cultivation without time-consuming and costly laboratory analysis. In addition, flowers with low THC content and therefore classified as “hemp” are now grown, dried and smoked just like high-THC flowers. “Smokable hemp” further blurs the distinction between drug and non-drug cannabis.

The 2018 Farm Bill is not to blame for confusion in terminology—it simply reflects shifts in public opinion and resulting changes in legislation. We can, however, consider alternative terms for cannabis products that more clearly explain their intended uses. By defining “hemp” as Cannabis plants and cannabis products containing less than 0.3% THC (in most countries) rather than by plant part and end use, “hemp” is now not just a fiber and seed plant, but also an industrial, chemical, and pharmaceutical crop.

A hemp grain seed field in Sweden.

A hemp grain seed field in Sweden. Highly aromatic CBG essential oil plants to the left of ‘USO-11’ EU-registered fiber plants, both with near zero THC content.

Highly aromatic CBG essential oil plants to the left of ‘USO-11’ EU-registered fiber plants, both with near zero THC content. Hemp textiles from Montenegro.

Hemp textiles from Montenegro. A hemp fiber harvest in Turkey.

A hemp fiber harvest in Turkey. A hemp fiber and seed harvest in Turkey.

A hemp fiber and seed harvest in Turkey. A field of CBD hemp in California.

A field of CBD hemp in California. A CBD flower.

A CBD flower.

Click Image to View Gallery

Redefining Hemp and Cannabis

The issue remains: How should we communicate about each product of the Cannabis plant? Although not a major concern for many individuals, shared terminology is important for promoting understanding between researchers, legislators, and the community. How can we best use terms to convey information so that we may all know what each other is talking about?

Which terms best fit low-THC Cannabis plants and their products? In light of the farm bill’s new definition of “hemp” and consequent changes in the use of “cannabis,” we offer several suggestions that may clarify the present-day situation and avoid further confusion:

- “Cannabis” as a genus name best encompasses the plant in all its botanical diversity as it has since the 18th century and should always be used when referring to the plant.

- The term “cannabis” is correctly used to denote differing products derived from Cannabis plants such as “adult use cannabis” or “medicinal cannabis” or “essential oil cannabis,” but we should avoid applying “cannabis” solely to THC-containing products.

- The traditional use of “hemp” was to describe the fiber and seed of the Cannabis plant, and this remains valid today.

- “True hemp” differentiates Cannabis fiber and seed plants and crops from other fiber and seed plants.

- “Hemp seed” or “hempseed” are directly associated with the “true hemp” Cannabis plant.

- “Hemp oil” should be used to denote the oil expressed from hemp seeds, and should not be used to describe any oils that contain CBD.

- “Essential oil hemp” best describes both low-THC Cannabis plants utilized for extracting essential oils containing non-THC cannabinoids and/or additional compounds such as the aromatic terpenes. “Essential oil hemp” can also be used to accurately describe all the products (other than fiber and seed) derived from low-THC Cannabis plants and crops.

- “Medicinal hemp” is only appropriate to describe low-THC plants and products with medicinal applications.

Though already well-aware of hemp’s long history, both von Linné and Lamarck would no doubt be surprised by today’s many uses for the Cannabis plant. And they should agree that it is up to us living in the modern age to embrace change by searching for and adopting terms that best describe diverse cannabis products and promote common understanding between many communities. English philosopher and physician John Locke (1632-1704) described our challenge thusly: “So difficult it is to show the various meanings and imperfections of words when we have nothing else but words to do it with.”