It would be safe to designate 2021 as the year of North American hemp fiber development. While fiber has been the hemp sector’s slowest to develop during the years following passage of the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (the 2018 Farm Bill), according to New Frontier Data, regional processing infrastructure and investment capital have been spurred by the myriad end uses of hurd and bast fibers from the stalk of the industrial hemp plant. New Frontier Data projects the U.S. hemp fiber market to grow at a 10.5% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) over the next five years to reach $77.7 million by 2025.

When industrial hemp production became fully legal in 2018, many U.S. oilseed processors had equipment that could easily handle food-grade hemp grain. Hemp fiber equipment had not been set up in the same way. In the U.S., a first mover in fiber processing was Kentucky’s Sunstrand, which ultimately filed for bankruptcy in 2019.

In the past 12 months, a handful of regional fiber processors have broken ground, including South Bend Industrial Hemp in Kansas, IND Hemp in Montana, BioPhil Natural Fibers in Pennsylvania, and Formation Ag in Colorado.

During the summer, industry watchers began to see committed acreage for hemp fiber production, particularly for agronomic research and development and feedstock creation to study hurd separation techniques. While such developments present new opportunities to local farmers within roughly 100 miles of the regional processors (anywhere beyond that would be too costly to transport), the markets for hemp-based fiber products are likely to develop piecemeal as both the capacity and quality of the supply chain slowly ramp up.

The first wave of hemp fiber products is hurd-based (e.g., animal bedding and absorbents), as they have the simplest processing requirements. As production techniques and processing advance, both the quality and breadth of material grades will increase. The second wave, which is in its early stages, will feature products that require larger scale or superior quality to produce (e.g., construction materials, particleboard, cellulose insulation, flooring, fiberglass substitutes, and nonwoven insulation).

As the U.S. hemp fiber supply chain matures, it will be able to supply a wide range of cellulose (a component of plant cell walls) products, industrial and consumer textiles, automotive components and other products at competitive prices compared to synthetic or other natural fibers. Price parity may be realistic over the next decade, especially if carbon incentives bolster hemp fiber and its end products. However, research into how much carbon various hemp fiber products can capture will take years.

For now, most hemp fiber-based products trade at a premium, but prospects are more promising as lumber prices continue to rise. In response to an especially damaging wildfire season, lumber prices from March 2020 to March 2021 rose 188% year-over-year, according to Random Lengths, a wood products industry magazine. This summer indicated wildfires are increasing both in frequency and magnitude. Combined with proposed environmental measures to cordon off large areas of forested land for logging, spikes in lumber prices will not be temporary, and hemp-based wood alternatives will continue to approach price parity.

As regional processing infrastructure develops, considerable effort is being made to advance the selection of hemp fiber genetics and farming techniques. Without established processors ready to handle material, it has proved nearly impossible to develop material specifications, crop standards, and standard operating procedures (SOPs) for planting, harvesting, retting, or baling hemp fiber biomass (i.e., plant stalks).

In 2021, U.S. fiber processors have partnered with farmers to trial an array of different hemp fiber varieties, targeting optimal crop yields and feedstock quality. While growers have trialed an abundance of European and Canadian hemp varieties in the U.S., those genetics performed poorly, according to Texas A&M University, due primarily to premature flowering (resulting in shorter plants) when planted at Southern latitudes (e.g., North Carolina and Texas), where there has been tremendous interest in the hemp fiber sector.

Fiber opportunists have been forced to look beyond Europe for industrial hemp varieties bred at latitudes farther south. This past summer, many U.S. hemp growers planted Asian and Australian hemp fiber varieties, which seemed far better suited for the Southern U.S., even reaching historic plant heights. As seen in university trials nationwide, however, the Asian and Australian varieties are not flowering. The discrepancy creates uncertainty as to how to propagate the varieties for planting seed.

While Asian and Australian hemp fiber varieties undoubtedly represent success stories as far as identifying suitable hemp genetics to grow in the Southern U.S., both an unstable seed supply and the challenge of harvesting a crop akin to a bamboo forest remain barriers to growth. Many a cautionary tale has been told in recent years about how an American row crop farmer’s equipment has fared when harvesting industrial hemp.

Even when harvesting a hemp crop for grain, there is the issue of wrapping. Though a combine used for wheat or corn can get through a hemp field to capture seed, complications arise when stalks wrap around its interior machinery. The high tensile strength of the plant’s fibers can cause a combine to overheat and fail. There have been recordings of combines catching on fire in North America, resulting in very costly repairs or total loss.

Though hemp-specific harvesters are available, an American farmer lacking a supply chain is unlikely to be encouraged to invest in specialized equipment. Compared to cannabinoids and grain, fiber (particularly hurd at $0.75 per pound) fetches the lowest margin. The choices are driving many farmers toward dual-purpose cropping, i.e., opting to grow varieties that grow tall enough to be baled for hurd after being harvested for grain.

Furthermore, the average price of a hemp bale is $150, with yields varying from as little as 1 ton per acre up to perhaps 10 tons an acre, according to New Frontier Data. Consequently, a farmer’s ROI for targeting a single-use hemp fiber crop is fickle at best. As mentioned, with processing only now reaching development, lower material prices come because of lower-value applications arriving first to market. More profits will come when hemp fiber processors attain the ability to decorticate the long bast fibers of the hemp stalk. Those fibers are high in cellulose, low in lignin, and used for weaving and spinning fabric for the textile industry.

RELATED: 5 Tips to Decorticate Hemp

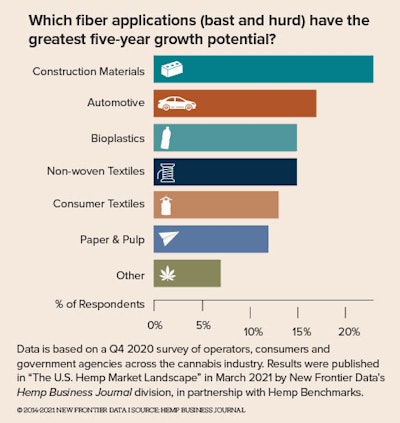

The capital for hemp-specific harvesting equipment could come from a farmer cooperative model or regional processors contracting production within a limited geographic radius. Currently, most operators are still raising funds to build their processing facilities, secure inputs like seed, or finance forward contracts; their shelling out of additional funds for harvesting equipment may be an afterthought. Despite high potential for growth in the coming years, fiber end markets remain uncertain as several different end applications strive for market acceptance.Which hemp fiber product categories will find their footing in the marketplace first? One metric to watch is price parity. The widespread adoption of hemp fiber is unlikely until there is price parity between hemp fiber products and comparable products made from less sustainable, albeit cheaper, materials. Another metric to track is how carbon credits for hemp fiber may help achieve price parity and disrupt various industries. In the short term, wood and plastic alternatives seem to be the categories best positioned for hemp’s widespread adoption and rapid growth.