Although she cannot change the past, Roz McCarthy still wonders today how her mother’s cancer treatment may have been different had she had access to medical cannabis.

Maggie Lois Smith, who began her career as a UPS driver in the 1970s, worked hard and pushed McCarthy to do the same so her daughter could be successful. “I never went a day not thinking and not knowing that I felt like I was her star,” McCarthy says now.

Diagnosed with breast cancer in late 2003, Smith passed away in early 2005. She was 54. McCarthy says the death of her mother felt more like the loss of a twin. Smith had McCarthy when she was 19, so they were close both in age and in their relationship.

McCarthy later learned about medical cannabis and thought it could have improved the quality of the end of her mother’s life, as Smith pushed through chemotherapy and radiation treatments and lost about 70 pounds. “I remember those days where she just could just barely hold down food,” McCarthy says. “I thought, ‘Man, this could have been an option.’”

That experience is part of what has inspired her to push for education about cannabis in communities of color and, more recently, for more representation of people of color in the industry.

She hopes now, as legalization and normalization grow, that cannabis can be a stigma-free option for her son, Bryan, who has sickle cell anemia. In the U.S., sickle cell anemia is most common among African Americans, with about one in every 400 African Americans being born with the disease, according to the Cleveland Clinic. Bryan, who now attends pharmacy school at Florida A&M University, doesn’t have a medical marijuana card to treat symptoms but does take cannabidiol (CBD).

“If he needs to use cannabis as a pain control option, I don’t want people looking at him thinking he’s just trying to get high because that’s not what he [would be] doing,” McCarthy says. “He’s trying to control his pain.”

These personal experiences, along with decades spent working in the health-care field, including writing grants for health-care facilities in medically underserved areas, stirred a new idea in McCarthy. In 2016, McCarthy founded Minorities for Medical Marijuana (M4MM) to provide resources to minorities who could use cannabis as a treatment option despite being possibly persecuted for it in the past or knowing people who had been. (She also consulted with and served on the board of the California Black Chamber of Commerce and consulted the African American Chamber of Commerce of Central Florida on business development.)

“I’m not a consumer, had never tried [cannabis],” says McCarthy, M4MM’s CEO. “I was just someone with a health-care background, 25 years of experience working in the health-care industry, and have my own personal experiences where I felt like, ‘Wow, this could be something that has to have some legs.’”

The nonprofit organization now has 27 U.S. chapters and international chapters in the United Kingdom, Jamaica and Toronto, McCarthy says. Its leadership and chapter presidents educate the public and lawmakers about the stigma around cannabis use and how to break it; aid those with marijuana possession charges to get their records expunged; teach entrepreneurs what it takes to run and manage a cannabis business; and work with cannabis stakeholders and government leaders to involve more minorities, women and veterans in the industry.

The war on drugs has led to the arrest and incarceration of disproportionate numbers of minorities in the U.S., including many for marijuana charges—and many criminal records and prison sentences that are still in effect today. For these and other reasons, many members of communities of color are still cautious to try cannabis. However, as cannabis’ benefits, both medical and economic, become more researched and understood, McCarthy and others are pushing for more access to product in communities of color and more minority representation in the industry.

Legislative Challenges.

McCarthy and others have succeeded in making advocacy and lobbying pushes to convince states and municipalities to set up social-equity programs for prospective business owners as well as diversity and inclusion programs for employees in the cannabis industry. These programs may include reduced application and license fees, and low-interest loan options for applicants, as in Illinois, or they may allow for priority application review, as in Massachusetts. Or, as in both of these states, they may provide technical assistance. But challenges to achieving equity remain, and not everyone agrees on one clear path ahead.

In Ohio, two judges have ruled the requirement to issue 15% of medical marijuana business licenses to “economically disadvantaged groups,” including minorities, unconstitutional. After the more recent ruling by a Madison County judge in November 2019, a spokesperson from the Ohio Board of Pharmacy said the 15% requirement is “no longer in effect.”

And prior to the state shutting down the requirement, the Board of Pharmacy spokesperson and another spokesperson from the Ohio Department of Commerce say, dispensary owners with a 51% or more stake in their business who were “economically disadvantaged” accounted for nine of the state’s 56 dispensaries. Meanwhile, two of the state’s cultivators and none of its processors came from these groups.

Illinois designed its social equity program to be “race-neutral” so that it can hold up in court, says Toi Hutchinson, senior adviser to the governor on cannabis control and a former state senator. But it addresses social equity in areas where people have been the most disproportionately impacted by the war on drugs and where many African Americans and Latinos live. To that end, the state created a “Disproportionately Impacted Areas” (DIA) map that plays a role in determining who can qualify as a social equity applicant.

“What we know about that population is that it’s 55% African American and 22% Latino that have been disproportionately impacted,” says Hutchinson, who played a large role in drafting Illinois’ legalization bill in her role as a state senator. “We know that. So, we designed an application, we designed a process, we designed a system that would try to get some of those folks the ability to come into this thing.”

Opening Access to Minorities.

Individuals and organizations are taking varying approaches to increase minority access to ownership in the industry and improve their chances of earning intergenerational wealth—but not everyone agrees on how exactly to do it.

McCarthy sees 5% or more as a sizable percentage of equity in a business entity. Owners with more equity or a controlling interest have more decision-making power, she says.

“Studies have shown that the more diverse a company is, the more profitable that company is,” McCarthy says. “If I were an investor and I wanted to invest my money, I want to have … individuals who understand how to build a 21st-century business that is in line with a Coca-Cola, Delta, United Airlines, [that value diversity] in that respect.”

Illinois reviews new dispensary license applications using a point system. In order to qualify for social-equity status, a business must have an owner who either comes from areas the state designated as “disproportionately impacted” by the war on drugs, has been charged with cannabis crimes that are eligible for expungement, or has family members who have been charged with such crimes. That individual must have a 51% or more stake in the company for the business to be a social equity licensee.

A social equity applicant also can be a business with 10 or more full-time employees, 51% or more of whom live in DIAs. Or it can have 51% or more employees who have been charged with crimes eligible for expungement, or whose family members have been.

The state’s legalization bill passed in May 2019, and cannabis sales became legal in the state Jan. 1, 2020. Many people, including in the industry, have applauded the state’s bill and its social equity provisions.

But others, such as members of Chicago City Council’s 20-member Black Caucus, expressed concerns that existing medical operators were the only ones the state approved to sell into the adult-use market on Jan. 1. Social-equity licenses will come online on or before May 1.

Jason Ervin, 28th Ward alderman and chairman of the Black Caucus, said prior to legalization in Illinois, African Americans have been disproportionately impacted by arrest and incarceration due to marijuana offenses, so they should be able to fully participate in the industry once it is legitimized. “We’re going to buy today, we’re in jail today, so why can’t we have equity today?” he asked.

In October 2019, Ervin introduced an ordinance to delay cannabis sales in Chicago until July 2020, with the goal of giving minorities access to the market share in the city. Two months later, that effort to delay sales failed. The state saw $110 million from adult-use cannabis sales alone during the first three months of 2020, according to the Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation. Sales were more than $1 million higher in March compared to February. On March 20, in response to the coronavirus pandemic, Gov. J.B. Pritzker announced a stay-at-home order but he deemed cannabis businesses “essential.”

Some cannabis-industry operators, like Illinois-based multistate operator Cresco Labs, have created incubator programs to aid social equity applicants. Cresco, through its Social Equity & Educational Development program, teaches people how to apply with the state for a dispensary license and provides them coaching and pro bono legal counsel, says Jason Erkes, the company’s chief communications officer.

“I think it’s important to note that you can’t go back and change the past, but you can take very aggressive steps to make sure that the future looks differently,” Erkes says.

Meanwhile, McCarthy and M4MM, through the nonprofit’s Cannabis Business Licensing Bootcamp, teams up with funding partners and cannabis companies, such as presenting partner Trulieve, to teach aspiring cannabis business owners about the industry. Education touches items such as how much compliance can be involved, how to read and understand application processes, how to build a team, how much products should cost in the supply chain and more. McCarthy and her team have held boot camps in St. Louis, Newark, N.J., and Chicago.

“They either decide, ‘Yes, I want to go forward,’ or they figure out, ‘You know what? No, this is not the right fit for me,’” McCarthy says. “And they now have made a really educated decision on where they want to get into the industry. Maybe it’s not at the touch-plant position—maybe it’s somewhere else. That’s what makes me happy, that people are not going and spending $6,000 for an application fee, when really and truly, that’s not what they want to do.”

A Second Chance.

To alleviate some of the damage done to people’s lives by prohibition, states across the country, such as Illinois, California and New York, are decriminalizing cannabis and expunging records.

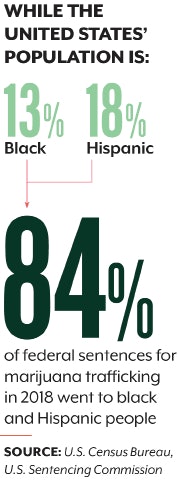

Across the U.S., minorities make up a disproportionate percentage of people who have been charged with cannabis crimes. African Americans make up roughly 13% of the U.S. population and Hispanics make up about 18% of the population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. However, black and Hispanic people received more than 84% of the federal sentences for marijuana trafficking in 2018, according to the U.S. Sentencing Commission.

In California in 2018, about 60% of misdemeanor marijuana arrests and 59% of felony marijuana arrests were of black and Hispanic people, according to state Attorney General Xavier Becerra’s office and the Department of Justice. This was slightly down from 2017, when those arrests were about 60% and 61%, respectively.

In New York, Gov. Andrew Cuomo previously vowed to push for adult-use legalization in 2020, but as of press time, he announced plans to cut that proposal in response to the coronavirus.

However, Cuomo signed a bill in August 2019 that downgraded the B misdemeanor of fifth-degree criminal possession of marijuana to the violation of first-degree unlawful possession of marijuana, according to the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services (NYS DCJS). The bill also downgraded the violation of unlawful possession of marijuana to the violation of second-degree unlawful possession of marijuana.

When these violations result in defendants taking plea bargains, having their fingerprints taken and getting convicted, the state automatically seals records. Convictions from prior to the passage of the August 2019 bill, for the charges that the state downgraded, are “automatically suppressed from civil ... or criminal inquiry response,” according to an NYS DCJS spokesperson.

Arrests of black and Hispanic people comprised about 80% of misdemeanor possession arrests in New York state in 2018, according to NYS DCJS. In 2019, that decreased slightly to about 75%, when the state downgraded the fifth-degree misdemeanor possession charge to a violation.

In late March, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, activists worked to clear jails of people awaiting trial for and convicted of cannabis-related crimes, says Sarah Gersten, executive director and general counsel for Denver-based nonprofit Last Prisoner Project. It’s wrong for people to remain incarcerated for something that many states are legalizing, she says, let alone to be confined in such close quarters with unsanitary conditions as an infectious virus spreads.

The Last Prisoner Project created a “Decarcerate Now” petition, directed to President Donald Trump and the Federal Bureau of Prisons, to convince the federal government to release inmates in the U.S. who have been convicted of cannabis crimes.

“Another thing that I think is critically important, because a lot of the focus is on the federal level, is for folks to contact their state and local officials, contact sheriffs and wardens of local jails, your governor, your state department of corrections,” Gersten says.

As of press time, some states and municipalities have cleared out jails and prisons, and others have chosen not to jail people for certain crimes.

In March, Virginia lawmakers in both the Senate and House voted to decriminalize cannabis. Gov. Ralph Northam’s deadline to vote on the bill is April 11, according to the Virginia Legislative Information System.

M4MM, through a new program called Project Clean Slate, plans to pull together attorneys and court clerks for expungement fairs, McCarthy says. However, it’s challenging to bring everyone together in one room. After the fairs, M4MM would like to offer wraparound services.

“They see the work that we’re trying to do to help clear their records with the hope that if they need any type of social services like resume-building, references for a job, workforce support, help to understand where to go look for [a job], health-care options, housing options …[what] we all need in regards to just being whole and being able to contribute to society—we want to offer that by having a full-time case manager who can … track them from the time they go in through our expungement program,” McCarthy says.

Cannabis providing a refuge for some communities.

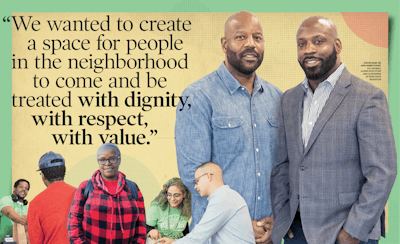

In early March, Kobie Evans and Kevin Hart opened Pure Oasis, Boston’s first adult-use dispensary and Massachusetts’ first minority-owned cannabis business. They received priority review for meeting Massachusetts Cannabis Control Commission’s “economic empowerment” criteria, such as setting up shop in an “area of disproportionate impact.”

Evans’ experience provides a glimpse at how aggressively policed areas during prohibition now allow legal cannabis business in those same communities. Growing up in Boston, Evans says police would “stop and frisk” him.

“They could stop you at any point, detain you, frisk you, assault you with impunity,” he says. “My story isn’t different than millions of other young black men. So, I don’t call myself a victim or act in a way as if I’m different from anyone else. It’s just a normal course of growing up in Boston and many other cities. Someone has to be the bad guy, and a lot of times, it ends up being a person of color—a young black man.”

Evans says the name Pure Oasis was inspired in part by the goal of providing a “sanctum” for people in Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood, where the 2,500-square-foot dispensary is located. More than 700 people came through on the business’s first day, March 9. Many of the sales that first week were of flower, Evans says, although Pure Oasis offered a broad assortment of products.

“We wanted to create a space for people in the neighborhood to come and be treated with dignity, with respect, with value,” he says. “In that instance, we wanted to create an oasis, where if you look in subsidized housing, and you look below the poverty line, but you wanted to come and buy something and feel like your dollar was valued, then, A, we wanted to create an oasis for you; and then B, we wanted to celebrate a product that is very organic and very natural and very pure.”

On March 23, to halt the coronavirus spread, Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker ordered adult-use dispensaries to close from noon EST March 24 until noon EST April 7. Evans said he understood that the governor’s response was in the public interest, but that the easiest solution for improving equity opportunities in the industry during this time is for states to deem all cannabis businesses essential.

Many customers using cannabis for medical reasons purchase in the adult-use market, Evans says. When Pure Oasis closed its doors on March 24, he says a customer approached him to share they were buying cannabis from Pure Oasis for their post-traumatic stress disorder.

“We’re going to buy today, we’re in jail today, so why can’t we have equity today?” Jason Ervin, 28th Ward alderman and chairman of Chicago City Council’s Black Caucus

“He applauded the fact that he can have access to a broad selection of product at our shop, but now he’s going to have to go back to the black market, and that’s reality,” Evans says.

As adult-use social equity programs come online, like those in Massachusetts and Illinois, McCarthy says she doesn’t want people to lose sight of cannabis’ medical benefits.

McCarthy wrote grants for the hospice and end-of-life industry. When she was writing them for Federally Qualified Health Centers, she used the Health Resources & Services Administration’s Medically Underserved Areas and Populations database to see which zip codes were medically underserved. “It would always be communities of color,” she says.

As scientists conduct more research into the medical benefits of cannabis, such as the effects of specific cannabinoids and terpenes, and work to improve patient outcomes through existing medical dispensaries, there’s a chance to better serve communities of color, McCarthy says. Dispensaries could carry cannabis medicine tailored to addressing specific conditions such as diabetes and cancer, which are prevalent in minority communities.

McCarthy also suggests that states could open pathways for social-equity applicants to open dispensaries in existing markets.

In addition to discussions about social-equity ownership in Ohio’s program, other conversations about medical programs continue, such as in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York and Florida. In Florida, M4MM is working with legislators on items such as setting up expungement fairs. On the West Coast, San Francisco’s Office of Cannabis requires equity plans from medical dispensaries in the city.

McCarthy believes advocating for social equity in the medical market is important because when federal legalization happens, legislators will prioritize the medical benefits of cannabis over adult-use. And Medicaid may end up being able to reimburse some purchases for people who need medicine, she says.

“They need to have something that’s in their community, that’s going to baby-step them a little bit, that’s going to show them the way, and also maybe reimburse them for their medicine,” McCarthy says. “It’s big thinking, but we need to be thinking big, and we need to be thinking long-game versus what we see tomorrow.”