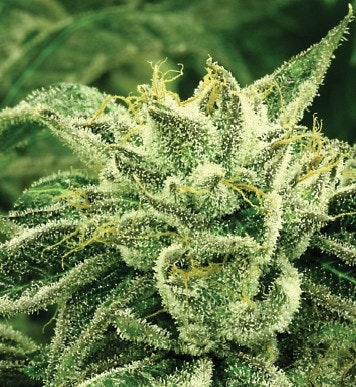

State health inspectors entered New Jersey’s largest marijuana dispensary in August. Tucked away inside a cabinet, they found a sealed container of pesticide.

Unused as it was, the container landed the dispensary in trouble, and highlighted an issue that is creating legal and regulatory waves across the industry, including a first-of-its-kind class action lawsuit in Colorado over the use of chemical substances to improve the quality and yield of the cannabis plant.

Garden State Dispensary (GSD) is licensed and legal in New Jersey, a state that allows patients to use medical marijuana for various health conditions. But growers are banned from using pesticides on plants, and regulators cited the dispensary even though it had not used the chemicals found.

GSD owner Michael Weisser told NJ.com in September that the dispensary had considered using the pesticide, but decided against it. GSD submitted a corrective action plan to the state health department, and it was approved without major consequences for the dispensary, which serves more than 3,000 of the state’s 5,500 medical marijuana patients. Weisser could not be reached for comment for this story.

Nationwide, cannabis is grown, labeled and marketed in wildly divergent ways because no overarching federal law dictates what growers can and cannot do to bolster their crops. The existing landscape of state and local regulations is a hodgepodge of horticulture and agriculture expertise, attempts at consumer protection, and testing methods that are often subjective and inconsistent, according to industry sources.

Federal regulators—the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the Food and Drug Administration—have made clear that they will not step into the fray over organic and pesticide-free product labeling and testing as long as marijuana is classified as a Schedule I illegal drug. Pesticide regulations for agricultural crops are typically set by the EPA under the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA).

Any national guidance for cannabis growing methods must be interpreted from existing laws, which explicitly require pesticides to be used only in ways consistent with their labels. The EPA told Washington State this year that some pesticides “may be legally used on marijuana under certain, other, very general types of crops [or] sites when there is an exemption from the requirement of a tolerance.” And the agency gave dispensaries the stop-gap option to register certain cannabis-related products as “Special Local Needs” under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA).

Legal Challenges

Industry players say the dearth of true federal regulation has created a market marred by rampant pesticide use, mislabeled products and uneven, unreliable testing methods.

It’s an environment ripe for lawsuits, and indeed the first case of its kind was brought Oct. 5 in Denver District Court against LivWell, one of Colorado’s biggest retail cannabis chains. The class action suit alleges that LivWell used commercial fungicide Eagle 20 EW on its crop. Eagle 20 is often used on fruit and hops, but releases hydrogen cyanide when burned. The city of Denver said earlier this year that pesticides approved for agricultural crops are not necessarily safe for marijuana, since cannabis is often smoked.

Colorado has maintained a list of more than 200 pesticides approved for use on marijuana plants, but this month proposed new, more restrictive rules that are currently under review.

LivWell said in a statement that it has never used a banned substance in cultivation: “We adhere to the most current rules and regulations regarding product labeling and cultivation as set forth by our regulators, including the Marijuana Enforcement Division and the Colorado Department of Agriculture. We believe the [lawsuit] is scientifically, legally and factually frivolous, and we will defend it vigorously.”

Eagle 20 was used “sparingly, at a time when many growers in the industry were using [it] to protect against harmful pests and diseases,” says Dean Heizer, LivWell’s chief legal strategist. “We made the decision to no longer use synthetic pesticides ... in the first quarter of this year, prior to Denver or any other regulator expressing a concern about it.”

Separately, Denver this summer placed a hold on hundreds of marijuana and marijuana-infused lozenges from Mountain High Suckers and MMJ America when they suspected the companies used pesticide including spinosad, which is now banned. Tests, however, did not show any spinosad residue; the retailers had apparently used old (leftover) labels that listed the pesticide. (Growers are required to list on labels any pesticides used.)

Both companies were required to buy new labels, and Colorado warned businesses with products containing now-banned pesticides that they must destroy the products or return them to the manufacturer.

Other States

Washington’s health department and State Liquor and Cannabis Board jointly provide a list of approved pesticides for marijuana growing. Washington tests for pesticides and other contaminants. USA Today found in 2014 that 13 percent of marijuana and other related products in Washington failed contaminant testing because they contained E. coli bacteria, mold, salmonella and yeast.

The Oregon Department of Agriculture (DOA) in August warned growers not to use illegal pesticides—which, in the state, includes nearly every pesticide available.

“It is important to note, pesticide applications that do not follow the pesticide product label pose risks to public health and safety and are a violation of state and federal law. THE LABEL IS THE LAW,” the DOA said in a letter sent to all legal marijuana growers in Oregon.

Other states offer simple guidelines. The Nevada Department of Agriculture, for example, only allows “minimum risk pesticides (also known as Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act 25b products)” to be used on marijuana. California issued marijuana pesticide regulations in April, designed in part to protect the state’s watershed. The state told growers that pesticides must be approved by the California Department of Pesticide Regulation and the EPA; the only allowable pesticide products allowed are “those that contain an active ingredient that is exempt from residue-tolerance requirements; and are registered and labeled for a use that is broad enough to include use on marijuana (e.g., unspecified green plants); or are exempt from registration requirements as a minimum risk pesticide under [the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act].” Further regulations exist for pesticide use when applied to an entire field, and for rodenticides.

“There are no pesticides registered specifically for use ... on marijuana,” California’s Department of Pesticide Regulation warned in a statement, “and the use of pesticides on marijuana plants has not been reviewed for safety or human health effects.”

What’s The Reality?

Growers, retailers and watchdogs interviewed for this story estimated that up to 80 percent of the cannabis products nationwide contain some level of pesticides, and most are not labeled accordingly.

Wildly different approaches, subjective measurements and a lot of inconsistencies exist. “It’s pseudo-science at best,” says an industry researcher/expert who wished to remain anonymous.

“It’s going to take time, and a lot of research,” says a grower who also wished to remain unnamed. “We don’t really know what it means to use these products on a plant that gets harvested and cured, and in a lot of cases smoked.”

Portland’s The Oregonian recently conducted extensive testing of marijuana products in the state and found almost all of them contained pesticide residue. Six months after the Colorado crackdown, a spot test by The Denver Post did not find pesticide residue on most products tested. But in one product that did contain residue, the amount of pesticide was more than six times the maximum level allowed by law on any food product. Colorado officials said this is a significant public health concern and that the state Department of Environmental Health is investigating.

Pesticide-Free, Organic And More

Labeling concerns are another wrinkle in the cannabis industry’s pesticide flap. While not addressing cannabis specifically—due to the crop’s illegal federal status—the USDA requires food products to meet strict standards to be labeled organic. False claims earn fines and citations.

“Depending on the severity of the violation, punishments can include financial penalties up to $11,000 per violation and/or suspension or revocation of the farm or business’s organic certificate,” according to a statement from the USDA. “A suspended or revoked operation can’t sell, label or represent its products as organic.”

In the absence of federal certification, the private sector has created several independent, third-party certification services.

Attorney and USDA-accredited organic certifier Chris Van Hook has been certifying cannabis products with a “Clean Green” label since 2004. His organization is based in Crescent City, Calif., and maintains a list on its website of certified operations. He says Clean Green uses an evaluation process similar to the USDA’s, but adds criteria on labor practices, water-conservation measures and other environmental concerns, to try clarify a generally murky market.

“Anybody can say anything,” Van Hook says. “The unregulated use of pesticides continues to be rampant. It’s a factor of cannabis continuing to be illegal. Finally, now that some states have legalized it, we’re starting to get concern from them, and from consumers, about pesticides.

“We need to start educating consumers, and consumers need to start using their dollars to make these choices,” Van Hook says. “States are starting to deal with the pesticide issue as part of the bigger picture. It’s following the exact same trajectory as any other agricultural crop would follow.”

Van Hook did not address specifics of the LivWell lawsuit, but says it will open the door to more legal challenges for more suits to follow.

Newer on the certification scene is the Denver-based Organic Cannabis Association (OCA) that is finalizing what it says will be rigorous organic standards to educate and protect increasingly savvy customers.

“We’re taking existing models in any number of other industries and applying them to marijuana,” OCA board member Ben Gelt says. “We aren’t recreating the wheel. But because the FDA and USDA aren’t coming in, ... it’s critical to offer guidance to a nascent industry.”

Because “some legal peril” exists in saying it will certify cannabis products as organic, says Gelt, OCA is starting with pesticides. Gelt says it has a handful of growers signed up for its soon-to-launch pesticide-free certification program.

He added that the OCA’s other work in sustainable agriculture supports the notion that cannabis consumers will grow more aware and selective as they have with food purchases. “People are going to Whole Foods willing to pay that 25-percent premium for their raspberries, but then they’re going to their dispensary and saying, ‘What’s good?’ [Historically] there was no ability to ask questions. It’s a new consumer product category where people still need to make these connections.”

Alison McConnell is an upstate New York-based writer and frequent Cannabis Business Times contributor. In her 11-year career as a journalist, McConnell has covered topics ranging from food to financial markets. Her work has appeared in newspapers and magazines, as well as on the radio and online. Dan McQuade is a writer for Philadelphia magazine. His work has also appeared in New York magazine, The Guardian, Vanity Fair, Playboy and other publications.