Note: This article originally appeared in Cannabis Business Times' August 2017 issue.

As our industry grows and attracts more botanists, horticulturalists and formally trained master growers, we need to be on the same page for our cannabis discussions. For clarity and uniformity, it’s important that we standardize our common language terms and use botanical terms correctly.

Common terms such as bud, cola and nug are often used interchangeably, whereas several botanical terms are misused more often than not. Here, we go over botanical features of the cannabis plant and identify its components to help cultivators use accurate terminology.

Common Usage

As I learned in the 1970s, the term bud and cola had qualitative differences in meaning. Decades later, nugs, another term for buds, became popular with indoor growers. All three—bud, cola and nug— consist of female cannabis flowers, yet all have unique characteristics that currently are losing their original distinctions.

Let’s begin with bud, the most popular and universally used word for marijuana. Botanists, speaking generally, use the term bud to mean any newly emerging plant part, appearing as no more than a nub or protuberance, whether it will become a branch, flower or leaf.

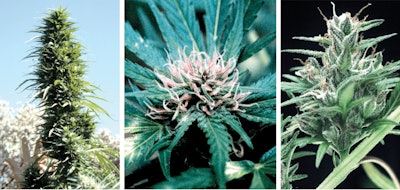

But in marijuana culture, bud refers to a distinct cluster of female cannabis flowers. Female flowers usually arise in pairs so tightly bunched together with succeeding pairs, that such pairing is apparent only in “running” buds most commonly seen in Southeast Asian landraces. Much more typical, female flowers grow tightly together, forming solid ovoid, pyramidal or teardrop-shaped clusters, usually about 1 to 3 inches long, and generally consisting of 30 to 150 densely packed individual flowers. The oldest flowers are found at the bud’s base, and the youngest at the top. Botanically, buds are racemes. (Editor’s note: In racemes, flowers grow along the plant’s axis.)

Cola, another commonly used term for female flower clusters, more often refers to an aggregate of buds that, having formed so closely together, looks like a single, very large bud. Colas form at the ends of stems and branches, and can be more than a meter long when grown outdoors or in greenhouses. Under lights, plant tops usually form colas no more than 8 inches long, particularly because plants are smaller, and canopies are restricted and trained to be uniform. Foxtail, another term for cola (cola is Spanish for tail), is rarely heard these days except from those whose history with marijuana goes back to the 1970s or 1980s. Most seasoned growers distinguish colas from buds. Nug (from nugget), another more recent term for a bud, more specifically refers to a manicured, dried bud, usually indoor-grown. Old timers rarely call a growing bud a nug, while more recent growers often make no distinctions, and call all buds and colas nugs, regardless of freshness, dryness or size.

Botanical

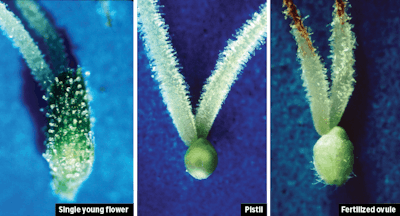

When discussing specific flowering parts, botanical terms are routinely used. And here, confusion reigns. Foremost is the common, incorrect use of calyx. Growers read or hear about swollen calyxes being a sign of maturity and an indication of readiness for harvesting. And growers, touting a favorite phenotype, will refer to its high calyx-to-leaf ratio, meaning that within the buds, flowers predominate leaves. But, what are incorrectly called calyxes or false calyxes are correctly identified as bracts. (See photo above.) The correct term should be bract-to-leaf ratio.

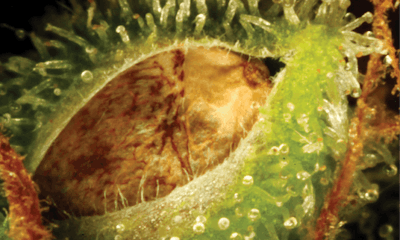

Female cannabis flowers do have calyx cells, but not a defined calyx. The female calyx cells are part of the perianth, a translucent, delicate veil of tissue (about six cells thick) that partially encloses the ovule (prospective seed). Each female flower has a single ovule, which is encapsulated by its bracts. The bracts are small, modified leaves that enclose and protect the seed in what some growers refer to as the seed pod. The bracts, with their dense covering of large, stalked resin glands, contain the highest concentration of THC of any plant part. Bracts make up most of the substance and weight of high-quality marijuana buds.

By definition, a perianth consists of a corolla and a calyx. In more familiar, showy flowers, the corolla is the collection of brightly colored petals we generally appreciate when looking at flowers, and the calyx often is the smaller green cup (sepals) at the flower’s base. Bright, showy colors, large flower sizes and enticing fragrances evolved to attract insects such as bees and flies, or animals such as birds and bats to collect and transfer pollen to other flowers. Cannabis flowers are not brightly colored, large or enticingly fragrant (at least to most non-humans); cannabis plants are wind-pollinated with no need to attract insects or animals to carry the males’ pollen to female flowers; hence, calyx and corolla cells never evolved into significant, attractive or showy parts.

Each female marijuana flower has two stigmas that protrude from a single ovule, which is enclosed by bracts. Stigmas are the pollen catchers. They are “fuzzy” (hirsute), about ¼-inch to ½-inch long, are usually white, but may be yellowish, or pink to red and, very rarely, lavender to purple. Many writers identify stigmas as pistils, and this, too, is incorrect. The pistil consists of all the reproductive female flower parts: two stigmas attached to an ovule. Each flower then has only one pistil but two stigmas. The term is misused in many books and seed catalogs that describe a single cannabis flower as having two pistils.

If pollinated, the ovule of each female flower grows into a single seed (an achene). The perianth, which, again, includes calyx and corolla cells, tightly clasps the seed and often contains tannins, which give mature seeds their markings. Spots, blotches and stripe markings are likely to be corolla cells. Between a thumb and finger, you can rub the perianth off of seeds.