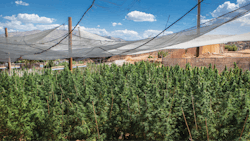

The bulk of California’s sinsemilla is grown outside. The natural harvest is in autumn, and summer has traditionally been a time of shortage. In 2017, wildfires across the state’s northern counties also limited clean flower supply; much of the outdoor production was tainted with smoke and soot. And as of July 1, cannabis flowers must conform to new rules and regulations, including stringent testing protocols.

Another reason for compliant flower shortage is the ingrained reluctance amongst experienced growers to navigate the bureaucracy of license applications for the chance of conforming to unfamiliar regulations. The regulatory process is daunting, compliance costs are high, and the wholesale price of sinsemilla is at an all-time low. There are simply not as many licensed growers as expected, and nowhere near enough to feed California’s massive retail market. And, many licensed growers are unable to sell their flowers to legal distributors because they fail the required tests for biological and chemical contaminants.

Although some growers fail the tests for potentially pathogenic fungi and bacteria, many more fail because their flowers contain agricultural chemicals.

Testing California

Federal and state governments set maximum residue limits (MRLs) for agricultural chemicals in food crops. These recommendations are designed for fresh, dried and concentrated fruit and vegetable products and form de facto guidelines for establishing MRLs for cannabis and other agricultural products.

The California Department of Pesticide Regulation publishes two lists of agricultural chemicals (largely pesticides) that have been detected in cannabis samples and will be controlled in commercial cannabis sales. Category I compounds are not approved for use on any food crops, and the state allows no residue levels of Category I chemicals in cannabis products. In practice, zero-tolerance levels prove to be unrealistic, as improved analysis techniques can raise detection limits from parts per million (which is the present standard) to parts per billion. Detecting traces of any chemical is largely dependent on the thoroughness of the search.

A quick survey of the Category I list shows that at least 44 agricultural chemicals are prohibited for use on cannabis crops. Several of these prohibited chemicals are monitored in a range of other crops, and MRLs have been established for each. However, Category I compounds are not allowed for cannabis use and therefore have no MRLs. Instead, they are assigned low detection thresholds of 0.01 to 0.02 ppm, which is about 10 times lower than most allowed pesticides’ MRLs. Under California guidelines, cannabis samples with any Category I chemical present cannot be legally sold.

(The most detailed listing of cannabis MRLs comes from California’s Bureau of Marijuana Control guidelines for medical cannabis testing laboratories and Department of Pesticide Regulation recommendations.)

Cannabis Challenges

Paclobutrazol (aka PBZ or Paclo), which has no permitted food use and a detection threshold of 0.01 ppm, is regularly detected in cannabis samples. Its use is only allowed on ornamental crops. Paclo is a plant growth regulator (PGR) that inhibits gibberellin plant growth hormone biosynthesis, thereby reducing internode growth to give stouter stems, and increasing root growth.

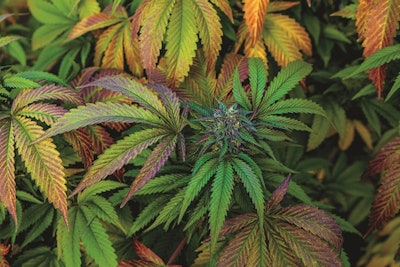

In cannabis, Paclo is added to a variety of nutrient products (e.g., PhosphoLoad, Gravity, Bushmaster, Flower Dragon, etc.) and is used by indoor sinsemilla growers to produce short and highly branched, dark green plants with extensive root systems and rock-hard buds. (Daminozide is another Category I PGR that is often included in nutrient products along with paclobutrazol.)

Imidacloprid is a commonly used general household insecticide sold under various brand names, and its MRLs are comparable to agricultural standards for fresh produce. Myclobutanil (sold as Eagle20 and Systhane) is a general fungicide widely used in the cannabis industry, and it is used with other crops in accordance with regulations. However, myclobutanil is considered a possible threat to groundwater supplies and is prohibited in California cannabis crops.

Several mite species present persistent problems in cannabis crops, and chemical sprays and drenches often offer the only effective and affordable control. Abamectin is a prohibited miticide commonly used on cannabis crops.

Our industry relies heavily on prohibited PGRs and pesticides that cause most regulatory compliance problems in California, and it is clear that at least with these four important agricultural chemicals, cannabis growers are subject to greater restrictions than fruit and vegetable farmers.

Several other agricultural chemicals are allowed for use on food and cannabis crops. California lists 24 Category II pesticide residues and their MRLs for inhalable and other cannabis forms.

Generally, MRLs set for inhalable cannabis are much lower than those set for other uses such as edible products, the MRLs of which are more in line with those of food products. Most of California’s residue regulations follow guidelines for other crops, though some are more stringent. As the regulatory climate surrounding cannabis production matures, we can expect to see some of these barriers lowered as policies become normalized in accordance with other industries.

Overprotective cannabis regulations, such as the Category I classification of paclobutrazol, might cause some cannabis products to fail residue screening; however, the indiscriminate use of allowable pesticides is a much greater cause for public concern and is addressed by strong regulatory controls and the establishment of MRLs. Cautious regulators are responsible for consumer health, and understandably they have set cannabis MRLs at low levels.

Good Cannabis Grown Right

Regulations alone are difficult to blame for flowers failing biological and chemical screening. Successful growers consider what it will take to produce a clean product and make every preparation to meet that goal.

The easiest way to comply with stringent regulations may be to practice organic agriculture, applicable to both small and large grows:

- If you don’t already have a set location, pick a site with ample sun, clean water, good soil drainage, adequate airflow and low air humidity to prevent mold and mildew problems.

- Build and maintain a living soil environment.

- Use low-impact integrated pest management strategies employing biological controls and environmentally friendly pesticides where appropriate.

- Spray biological controls, such as Bacillus thuringiensis (BT) bacteria, for bud worms.

- Trap rats.

- Fence out rabbits, deer and other mammals.

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

When growing indoors or in greenhouses, cleanliness is of primary importance. Sterilize all work areas and tools regularly to prevent the spread of invisible fungi and bacteria. Maintain only healthy, pest-free mother plants. Be sure starter cuttings are completely pest-free before using them to grow mother plants. If you are experiencing persistent pest problems in your mother plants, consider starting again from seeds.

Some allowable pesticides are systemic and are taken up by every plant part. Many take a long time to break down, so they can exceed their MRLs even after several cutting cycles. Many growers who fail residue tests claim to have not used any chemical inputs on their crops. Apparently, some pesticides are so long-lived that plants produced in a grow room or greenhouse where pesticides were used even months earlier can be tainted, and may not pass MRL screening. (Read more about clones at risk for pesticide residues in our May 2017 issue.)

As a last resort, apply chemical controls well in advance of taking cuttings in accordance with the product label and long enough before harvest to ensure that only allowable residues remain in the dried flowers. And, consider that in agriculturally zoned areas, neighboring growers of established food crops may apply chemical controls that effect the levels of prohibited or controlled compounds in nearby cannabis crops.

Other Reasons for Failure

Regulatory enforcement is a strong determinant of which cannabis products become most readily available, and we increasingly live in a concentrates- and extracts-dominated world. During the sudden normalization of cannabis products, traditional dry-sieved hashish and even modern water-sieved hashish have largely been forgotten. Sinsemilla flowers’ decreased availability is matched by increases in vape pen flavors and market share. Solvent extracts are only the most recent manifestation of cannabis concentrates.

Traditional labor-intensive, mechanical-concentration techniques, and their benefits, have been superseded in our modern age by the manufacturing ease and huge volumes achievable with solvent extraction (e.g., alcohol, butane or carbon dioxide). Extracts may offer growers a way to profit from inferior, immature or biologically contaminated flowers, but solvent extraction also concentrates chemical contaminants such as pesticide and solvent residues along with THC, CBD and terpenes, leading to failed MRL screening. That said, forward-thinking companies are developing strategies to purify extracts and remove pesticide residues.

What’s to Come?

Neither MRLs, nor growers who fail to comply, are entirely responsible for the lack of legal, high-quality flowers at reasonable prices. And, because of regulatory compliance, many growers are upping their games to compete in the legal market, and thereby bringing long overdue, environmentally positive changes to our industry.

On small, biodynamic farms, relevant agricultural technologies and management strategies come to fruition. Successful fruit and vegetable growers benefit from well-practiced skills of producing naturally grown and pesticide-free crops for boutique markets. And, pioneering craft cannabis growers can share in the same benefits, while preserving the heritage cultivars that discerning customers pay extra to enjoy. The future for innovative, small growers is bright and sunny.

Although some regulations are presently over-protective, and in serious need of adjustment to agricultural norms, the effects of legalization generally have been healthy. As the regulatory climate matures, we expect more consumer-friendly and industry-appropriate MRLs will be established for cannabis, as they have been for more familiar crops. Formerly naïve consumers are now aware that there can be increased health risks associated with unregulated cannabis. Legal cannabis states are enforcing regulations to protect consumers, and producers are seeking cannabis cultivation solutions with fewer artificial inputs. The sinsemilla market will continue to evolve, apace with regulatory compliance and consumer preferences, so our beloved flowers should be around to serve us well into the future. Be patient. California will blossom again.