When Cole Cacciavillani and John Cervini, co-founders of Canadian licensed producer (LP) Aphria—pronounced ah-FREE-ah—laid eyes on their first commercial cannabis crop in 2015, the duo looked at each other and said, “How are we going to sell 10,000 square feet of this stuff?”

While this type of question might get a wry smile and a chuckle from many experienced cultivators, the co-founders had little commercial cannabis experience prior to launching their company. Both Cacciavillani, also VP of growing operations, and Cervini, also VP of infrastructure and technology, have backgrounds in the commercial greenhouse industry, but only Cacciavillani had cannabis knowledge prior to 2012. He became a designated grower for four patients under Canada’s caregiver program, the Marihuana Medical Access Regulations (MMAR, for short).

Cacciavillani had an interest in the cannabis industry since medical marijuana was made legal in Canada in 2001, but never saw an opportunity for commercial viability until the MMAR’s inception. When that happened, “I wanted to start to play with this plant and see what it does and what it is and how it acts,” he explains, “because I am not ‘of the culture.’ I’ve never smoked it, didn’t even know it had a bud. I thought you smoked the leaf.”

Needless to say, neither of them found they had any problems selling the fruits of their first crop. In fact, they found they could not supply enough of it, and added former Jamieson Laboratories (a popular Canadian brand of health supplements) CEO Vic Neufeld to their executive team to help build their business.

Today, Aphria is a publicly traded company on the Toronto Stock Exchange, cultivating in 100,000 square feet of greenhouse space, after a second greenhouse with over 55,000 square feet of canopy was approved for plants May 12. More importantly, the company’s low-cost approach has given the trio the ability to add another 900,000 square feet within the next 18 months, which will bring Aphria’s canopy footprint to a whopping 1 million square feet (all greenhouse space). Add to that the company’s foray into the American market, and you have the makings of a cannabis titan.

Trust Your Team

One takeaway you get from talking with Cacciavillani, Cervini and Neufeld is how much they all trust each other.

The three executives hail from Leamington, Ontario, Canada, a vibrant farming community with the largest concentration of greenhouses in North America and home to Aphria. Cervini and Cacciavillani knew each other for years through the tight-knit greenhouse community; Cacciavillani and Neufeld went to high school together.

When Neufeld left Jamieson Labs after 21 years at the head of the company, his plan was to ease into retirement and enjoy some of the wealth he had accumulated over the years. A day had not gone by before Cacciavillani and Cervini reached out to him to oversee the front office of their new medical marijuana company.

Neufeld accepted, but on one condition: only if he could build the executive team as he saw fit.

This might have caused many other people to baulk, but Cacciavillani says that he and Cervini felt comfortable relinquishing control of the front office because of those years building familiarity and trust. “I know Vic, he’s the executer of my will and everything. I trust the guy like a brother,” he explains.

While the co-founders take a step back from managing the day-to-day front office, they all make big-picture decisions together. “We drive it as a group, but Vic executes,” Cacciavillani says.

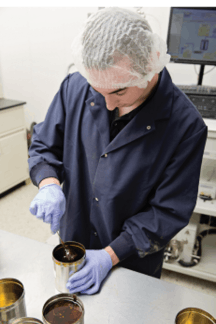

Neufeld turned to people he trusted, as well, to build the front office: the company’s comptroller (financial controller), chief science officer, director of quality, and many lab techs were all former employees of his at Jamieson Labs. (Because he had signed a non-compete agreement, Neufeld couldn’t solicit those employees, but instead waited for them to leave the company on their own before approaching them.)

“I went to the people that I knew and mentored over years, trusted, understood their competencies and brought them over,” he says.

Low-Cost Cannabis

This combination of commercial agriculture experience and pharmaceutical laboratory efficiencies is what allows Aphria to operate at nearly half the cost of their Canadian competition, according to Neufeld.

“We are somewhere around $2.00 [Canadian] a gram in terms of all-in costs,” Neufeld says. “So that’s the cannabis grown, dry[ed], process[ed], tested, packaged in the bottle and out the door.”Growing in a greenhouse was imperative for Aprhia’s co-founders; cultivating any other way was never a consideration. Cervini says by using greenhouses, “we’re maximizing nature and using nature to its fullest, and that really helps to drive our position of low-cost.”

Aphria does use supplemental lighting, but only when necessary. With Leamington being the southernmost point in Canada—it’s at the same latitude as Northern California and Rome, Italy—those supplemental lights do not even need to be at maximum intensity. In fact, Cervini needs to use shade curtains during the summer months when the cannabis plants enter flowering. Neufeld says what Aphria spends in electricity bills in one year is what large indoor LPs pay in a month.

That’s not to say that cutting down on supplemental lighting has not come back to haunt the co-founders: This past winter was particularly warm and cloudy, and the greenhouses didn’t have enough supplemental lighting, which hurt their yield. Cacciavillani will be adding more supplemental lighting units in the new greenhouses once construction begins on those.

Currently, he uses a mix of HPS and LED lights, but the new greenhouses will be equipped with LumiGrow LEDs that have a focus on red and blue spectrums. Since the sun acts as the main source of lighting in the greenhouses, Aphria doesn’t need to use full-spectrum lights, Cacciavillani says.

Aphria also cuts electricity costs by foregoing air conditioning or any cooling pad systems. Instead, Cervini and Cacciavillani use the natural ventilation of the greenhouse structures.

Glass panels on the greenhouse can be opened to allow air to circulate from one end to the other, and “the cannabis plants themselves, through transpiration, cool the greenhouse,” Cervini explains. “Through photosynthesis, [the plant] moves water through itself and pushes it out into the air, and when it does that, it actually cools the greenhouse.”

He says when temperatures reach 90°F outside, it is around 87°F in the greenhouse; the plant[s] [don’t] mind the slightly higher temperatures because they are getting an equally high amount of sunlight, increasing photosynthesis and transpiration.

Both VPs also run a tight ship when it comes to moving plants from one stage to the next. Everything from workflow to strain selection is done to maximize efficiency.

Aphria harvests six times per year and runs on an eight-week harvest cycle. This means a cultivar that takes 11 weeks to flower will not be found in Aphria’s lineup. Aphria harvests between 50kg to 60kg per week, and it takes the company 20 weeks to move its product from clone to sale, Cacciavillani says.

Aphria’s operations have been modeled after Cacciavillani’s and Cervini’s other businesses: Everything has been optimized for efficiency and output. Once optimized processes are in, “it’s very easy to lower costs,” Cacciavillani says.

The 100-Factor

Expanding an operation 100-fold within 4.5 years of being licensed, while maintaining low operational costs, requires more than opening windows and letting plants sweat, which is where Cacciavillani and Cervini’s expertise comes into play.

Cacciavillani takes the same approach to cannabis as he would any other plant. He knows many cultivators will cringe at his words, but quickly adds, “I’ll tell you a tomato and a cucumber are the same, but obviously, they are not. But we handle them the same.

“If you grow based on science, you’re growing the same. ... You still need certain nutrients at a certain time in their life cycle, you need water, you need CO2, you need the right climate—all that stuff is the same, just different,” he says.

The co-founders, therefore, are bringing the technologies and scientific processes from commercial agriculture into their cannabis cultivation. For example, Aphria mixes its own growing medium in-house; using a long conveyor belt with large bins containing the separated ingredients speeds up the mixing process.

The mix is a peat moss-based proprietary blend Cacciavillani has been using for years as a potted-plant grower. Other ingredients include sand, vermiculite and fertilizer.

The company mixes its own growing medium for two reasons. “We buy bulk right from the manufacturer, right from the field, and we can control all [the inputs in our medium]” Cacciavillani says. Second, Cacciavillani and Cervini can tweak the recipe from one season to the next.

“In the winter, we blend it in such a way that it has a higher porosity, so it actually holds less water, and we get better root growth in the winter when you’ve got a few more cloudy days,” Cervini says. “In the summer when it’s really hot … I want to hold more water, so I blend it differently.”

Automated potting machines and robotic transplanters are other pieces of automation that are going to help Aphria cut its labor costs. Cervini has plans for a system that would “bring the plants to the people, and the people will stay stationary.” Two-tiered conveyor belts to facilitate and accelerate the trimming process also are being added this summer.

As for automated environmental controls, Cacciavillani and Cervini went with something they knew: a Priva system commonly used in the commercial agriculture industry for more than 40 years.

The software gets updated regularly, “but the actual fundamentals of how we operate and what we do really doesn’t change,” Cervini says. “The heating and how it works, … irrigation and things like that are all very standard commercial agricultural tools and equipment.”

The company expects the biggest challenge in expanding to 1 million square feet of canopy will be “ramping up the labor force,” according to Cervini. He says getting good middle management (floor managers, directors, supervisors) is critical to a successful expansion.

“We’re mitigating that challenge with automation and being in the right location where we’ve got a good talent pool around us that can manage it,” Cervini says. “It’s a challenge, but it’s a challenge that we’re very well-equipped to manage.”

Dealing With Canada’s Pesticide Problem

Another area of expertise the co-founders built during their traditional, commercial agriculture days: Integrated Pest Management (IPM).

In the last six months or so, several Canadian LPs have faced recalls for products tainted with banned pesticides, including myclobutanil. Aphria has avoided such trouble because of Cacciavillani and Cervini’s unique experiences, according to the co-founders.

As a food producer, Cervini had very limited options to treat his produce if anything went awry. More often than not, he would turn to predatory insects to fight any pest problem. His partner’s experience is quite the opposite: Not many people want to buy potted plants filled with insects, so Cacciavillani has extensive knowledge on which pesticides to use and, more importantly, which ones to avoid.

While Aphria does use pesticides from Health Canada’s approved pesticide list, much of the work is done with locally sourced biologicals. Home base for one of the world’s largest suppliers of biologicals, Biobest, is in Leamington.

“[Biobest is] rearing the biological right next door, basically, and we get them fresh,” Cervini says.

Cacciavillani also credits the proprietary growing medium he uses as a contributing factor to the company’s IPM success. “When you use the proper growing media, you can set up your own little biosphere in [it],” he says. “Good bacteria eating bad bacteria.”

Other measures taken include sticky cards checked daily to scout for pests, and frequent cleaning of the greenhouses’ cement floors. The ebb-and-flow floors allow employees to quickly clean them with a hose without having to worry about stagnant puddles forming, as the curved floors drain the water toward the sides of the structures.

Go Big or Go Home

The team focus on low-cost, commercial greenhouse production has gained them attention from their southerly neighbors, and as the company CEO and unofficial “plan executer,” Neufeld has been a key factor in the company’s international growth.

In his time at Jamieson Labs, Neufeld grew the company from a single-market distribution to having Jamieson Labs products in over 40 countries. While there are differences between the cannabis market and the nutraceutical industry, Neufeld’s strategy was similar.

“When we look[ed] at penetrating a new country, we looked at a number of factors,” Neufeld says, “but one factor … I wanted was government regulation that spoke to our strengths.”

Aphria was very careful in choosing which markets to enter. For example, canopy limits were a major deciding factor, according to Neufeld.

“Our whole concept to our shareholders is if we can’t go big we’re going home,” he says. “So for us to penetrate those states and only have 10,000 or 20,000 square feet of growing was not what was part of our DNA.”

When a group from Snowflake, Ariz.—with a deal in place to buy a 40-acre Dutch greenhouse to grow medical cannabis—approached Aphria about sharing the Canadian company’s intellectual property, Neufeld began studying the Arizona market. He saw doctors were quickly buying into the program, the regulatory framework allows for large-scale cultivation operations, and, most importantly, it was a medical-only market.

When Neufeld and the team looked at other states, he says, “we quickly came to realize that where there’s recreational and medical, it’s not where we want to begin,” because those markets are already saturated. Arizona was a near-perfect situation in which Aphria could expand, and a deal was made in October 2016. At press time, Aphria owns 22 percent in Copperstate Farms and has retrofitted eight of the 40 acres of available greenhouse space.

It also has a management agreement with a licensee in Florida, Chestnut Hill Tree Farm. Aphria will eventually own the license.

Despite similarities in his approach to both markets, Neufeld has been feeling the difference between his Jamieson Labs career and the breakneck speed at which the cannabis industry operates. “I had many years at Jamieson to build that infrastructure, those SOPs, etc. Where today we’re racing to get there in a much shorter time frame,” he says.

“We’re going to get there. It’s going to take some time. But to stay committed to the program, to stay committed to that vision is going to be long-term success for us.”