The couple was driving east on I-84, in October 2017, when a state trooper flashed his lights and pulled them over. They weren’t from around here, in southern Idaho: He was from New Jersey, she was from Florida. In the back of their SUV, a stack of suitcases, duffel bags and plastic totes were found stuffed with 215 pounds of cannabis.

"The amount of marijuana we seized last year was more than the previous three years combined, and with that there was a significant [increase] of very large seizures. One up in the Coeur d'Alene area [was] almost 400 pounds," Idaho State Trooper Steve Farley told KTVB at the start of 2018. For Idaho and other neighboring states, Oregon’s overproduction problem has become their interstate trafficking problem.

Oregon’s licensed growers are currently producing more than 2 million pounds of cannabis each year. The in-state demand for cannabis, however, is between 186,100 and 372,600 pounds, according to the federally funded Oregon-Idaho High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (HIDTA) 2018 Marijuana Insight Report.

It’s that sort of ratio that led U.S. Attorney Billy Williams to issue a series of forceful statements about the state’s sprawling cannabis industry. (The HIDTA report includes legal market production totals and illicit market production estimates.) In representing the District of Oregon, Williams’ top priorities in enforcing cannabis laws are to preserve public safety and deter crime—namely, by preventing legal cannabis products from being funneled out-of-state through illicit markets. That’s called “diversion” in the cannabis industry. By Williams’ own estimation, it’s not going so well in Oregon.

Between July 2015 and January 2018, 14,550 pounds of Oregon cannabis was seized en route to 37 states. The products totaled $48 million in value.

But that’s just a fraction of the oversupply problem. As of 2018, according to the Oregon-Idaho HIDTA report, “only 31 percent of available cannabis inventory was distributed [in-state], leaving 69 percent unconsumed within the state-sanctioned recreational system.”

Williams has made this disparity a top priority for his office.

“What is often lost in this discussion is the link between marijuana and serious, interstate criminal activity,” Williams wrote in August. “Overproduction is rampant and the illegal transport of product of out of state—a violation of both state and federal law—continues unchecked.”

Oregon’s licensed growers are currently producing more than 2 million pounds of cannabis each year. The in-state demand for cannabis, however, is between 186,100 and 372,600 pounds.

But cannabis farmers in Oregon say that the solution won’t be found in crackdowns and arrests. The FBI has already zeroed in on a number of diversion schemes, mostly by investigating apparent credit fraud stemming from Oregon businesses. Still, overproduction persists.

The Oregon Liquor Control Commission put its licensing process on hiatus this summer, but not before it was flooded with prospective business applications. And still, the state’s licensed cannabis industry is producing the full gamut of adult-use products at a rate well beyond its consumer demand. (In late August, the OLCC abruptly dropped the daily medical marijuana purchase limit for patients—from 24 ounces per day to one—to further reduce any potential diversion into the illicit market.)

As of September 2018, the OLCC had licensed more than 1,000 growers. When Williams issued his statements about the cannabis industry this year, his language was aimed directly at those businesses—that “weakly-regulated industry,” as he said.

“I wish his rhetoric was a little more was more nuanced,” Adam Smith, director of the Craft Cannabis Alliance in Oregon, tells Cannabis Business Times. “And I wish that he was discussing this from an angle that was better informed of the bigger picture. But I don't want to turn Billy Williams into a villain, right? I mean, he is the federal government's prosecutor here. And, you know, whether we agree or not [that] things are out of control here or if there's just a problem, clearly we have an oversupply issue in the legal market.”

When combined with the illicit market, the total amount of cannabis being produced in Oregon is vastly outpacing even the most liberal in-state estimates of demand. The OLCC’s new tact is one path to slowing that production growth, but industry stakeholders are still looking for some sort of legal outlet for the market. “Cannabis has been exported out of the Pacific Northwest for generations,” Smith says. “And the question now is, do you have an opportunity to direct that cannabis into the legal markets?”

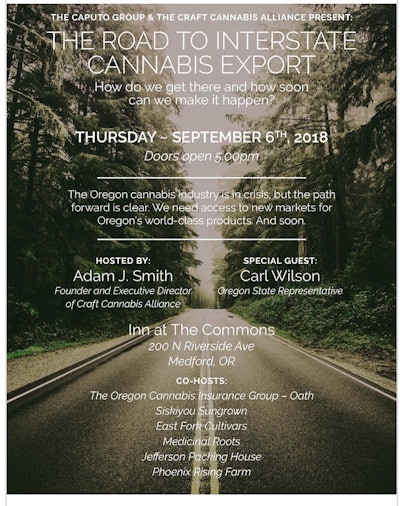

On Sept. 6, Smith’s Craft Cannabis Alliance invited State Rep. Carl Wilson and hosted an event in Medford that explored the topic of interstate export and debated what that might look like in Oregon and in the U.S. in general. Wilson discussed how the state legislature might play a role in getting this ball rolling nationally. The way Smith describes it, legal cannabis exports from Oregon to states that use the same tracking software (like Ohio or Massachusetts) would relieve pressure on the Oregon market and would allow those other states to import high-quality flower and focus solely on retail regulations. It’s an industry overhaul, but it’s a move, he says, that would straighten out the nascent fragmentation of the domestic cannabis market.

Wilson and State Sen. Floyd Prozanski have both publicly supported calls for cannabis export policies. Neither lawmaker responded to CBT’s request for comments for this story.

“We have hundreds of millions of dollars of local capital here that's on the verge of disappearing,” Smith says. “And, you know, some of that is … people who don’t know how to run businesses and they were going to go out of business anyway. But a lot of that is folks who are growing some of the best product in the world as efficiently as anyone—there's just no real market for it here, right? You have, really, an economic calamity that's happening in front of us.”

Smith paints a picture that distinguishes the legacy cannabis markets of northern California and Oregon from other states that are presently licensing large-scale indoor grow facilities—and at a slower rate that what the OLCC has done.

“We're in this moment where you have the governor of New York turning around … and saying ‘OK, well, we're definitely going to legalize, it's only a matter of how,’” Smith says. “Well, ‘how’ can't possibly be having New York set up a production industry larger than Oregon's from scratch, right? In a place [where cannabis] doesn't really grow, and having New Jersey do the same thing right next door … when you have the West Coast, where we have world-class product rotting on shelves that we can’t sell.”

Offering a comparison to many other national industries, Smith says that a post-prohibition domestic market would see states taxing and regulating retail sales of cannabis products grown and manufactured where it’s most economically feasible. “If the federal government really wants to limit the amount and is so concerned about oversupply,” Smith says, “why would you, through your policies, mandate creating more supply?”

With public events held across Oregon recently, Smith’s Craft Cannabis Alliance has helped push interstate commerce to the top of the industry’s political agenda. He’s hoping that this is recognized on a broader level, before too many small Oregon cannabis farms find themselves pushed out of the legal market. What it would take at first, he says, is legislation in Oregon to begin this process of allowing interstate cannabis exports. Then it becomes a national conversation, and the industry will look to other states for acceptance.

Mason Walker, CEO of East Fork Cultivars, says that this is one way of advancing the cause of national cannabis reform and supporting the state’s economy. (East Fork Cultivars co-hosted the Medford event on cannabis exports.)

“We’re definitely huge proponents of interstate sales,” he says. “I think it’s a no-brainer—a really good solution to our immediate issues with supply and demand imbalance in many states. Nevada has a massive quality cannabis shortage right now, and Oregon has an abundance. Just even matching those two states would be a boon for both.” (Nevada uses BioTrackTHC for its seed-to-sale tracking.)

Just by having these sorts of discussions now, Oregon finds itself at the vanguard of the interstate sales movement in the U.S. cannabis industry. For Walker, he returns to the same local economic talk that propels Smith’s arguments.

“It’s an inevitable future,” Walker says. “I think it’s just a matter of time until we see some movement on the federal level that either makes a clear path for states to legalize and allows them to do business with each other or just completely … makes a more clear path for legalization at the federal level.”

Top photo courtesy of Adobe Stock